Of the seven names signed on the proclamation of the Irish Republic, as read from the front of the General Post Office (GPO) in Dublin on 24 April 1916, only one name stands alone and above all the rest. Ironically, some of the best known figures of the Rising today are actually amongst the later signatories; despite being President of the Provisional Government, Padraig Pearse is the fourth signatory; James Connolly is relegated to the sixth position. The man accorded the honor of being the first to sign the document that ushered in a new era of freedom for Ireland is today probably one of the least well known; Thomas Clarke. Yet even a brief examination of his life reveals why he was held in such high esteem by men whose name is synonymous with Irish patriotism and why Clarke should be better known today.

Of the seven names signed on the proclamation of the Irish Republic, as read from the front of the General Post Office (GPO) in Dublin on 24 April 1916, only one name stands alone and above all the rest. Ironically, some of the best known figures of the Rising today are actually amongst the later signatories; despite being President of the Provisional Government, Padraig Pearse is the fourth signatory; James Connolly is relegated to the sixth position. The man accorded the honor of being the first to sign the document that ushered in a new era of freedom for Ireland is today probably one of the least well known; Thomas Clarke. Yet even a brief examination of his life reveals why he was held in such high esteem by men whose name is synonymous with Irish patriotism and why Clarke should be better known today.

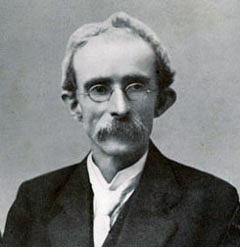

Thomas Clarke’s early life was an unlikely start for a future Irish rebel. He was born 11 March 1858 on the Isle of Wright to an Irish Protestant father from Leitrim who was a career British Soldier, and an Irish Catholic mother from Tipperary. The first seven years of young Tom’s life were spent living in various garrison towns throughout the British Empire until in 1865 the senior Clarke was transferred to Dungannon, Co. Tyrone; a place Clarke would always regard as home.

While in Dungannon, Clarke became an ardent supporter of Irish independence and met John Daly, the local organizer for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), and was soon sworn into the IRB in 1878. On 15 August 1880 a riot broke out when members of the Orange Order attacked members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians who were parading to celebrate the feast of the Assumption. The Royal Irish Constabulary intervened by opening fire on the crowd, killing one of the Hibernians. The following night, Clarke and up to four other members of the IRB attempted a failed ambush on a group of RIC in retaliation. Facing imminent arrest, Clarke decided to immigrate to America.

Arriving in New York, Clarke took a job as a porter at a Hotel in Brooklyn and seemed well on his way to success in his new Country; eventually being promoted to manager. However, Clarke’s heart remained firmly in Ireland and devoted to Irish independence. Shortly after his arrival, he had made contact with the Irish American organization Clan na Gael which, under the leadership of the consummate Fenian John Devoy, worked in conjunction with the Irish IRB for the cause of Irish freedom. Clarke was ordered by Devoy to engage in a secret mission to England. Unfortunately, what neither Clarke nor Devoy knew was that Clan na Gael and the IRB had been effectively infiltrated by British intelligence and was riddled with informers and agent provocateurs who were actually coordinating Clan na Gael missions with the goal of entrapping its members and discrediting the cause of Irish nationalism. Tom Clarke, traveling under the alias of Henry Wilson, was soon captured, found guilty of treason and sentenced to life in prison.

Even by the cruel standards of the dark demonic world of a British Victorian prison, Irish prisoners such as Clarke were singled out for particularly sadistic treatment; they were kept in isolation except for an exercise period and were forbidden to speak to anyone at any time. Their isolation from the general prison population allowed the guards to engage in systematic abuse of the prisoners ranging from severe beatings to sleep deprivation. Many, including two of Clarke’s comrades, were broken and went insane. For 15 years Clarke endured until his parole in 1898. While the strains of his confinement had prematurely aged him, he retained his sharp mind while developing, if possible, into an even greater foe of the British government. The esteem felt for Clarke in Nationalist circles was unequaled because of his suffering for the cause.

Clarke returned to America and married Kathleen Daly (who would become a formidable Irish patriot in her own right), the niece of John Daly, who initiated him into the IRB, and was 21 years his younger. Again Tom seemed well on his way to the American dream, in a few short years he was able to purchase a 60 acre farm in Mannerville, NY. However, to Clarke, his personal prosperity was secondary to his devotion to Ireland and her people. He returned to Dublin in 1907,many believe at the request of John Devoy, with the goal of reviving the IRB and the cause of Irish Nationalism, both of which were flagging. He purchased a Tobacconist Shop, ironically located at 75a Great Britain Street, which soon became the hub of Irish separatist activity.

While Clarke was extremely disappointed in the IRB leadership he found on his arrival, he took great hope in the new wave of Irish patriots who were coming from the traditions of the GAA and Gaelic League. Clark observed that they were “a splendid set of young fellows. . . who believe in doing things, not gabbing about them only. I’m in great heart with this young, thinking generation. They are men; they ’11 give a good account of themselves“. Clarke soon identified great talent in these young men such as Sean MacDiarmada and a schoolteacher famed for his oratory named Padraig Pearse, who, among others, would go on to fame in 1916. Ironically, while looking like a grandfather himself, Clarke systematically succeeded in removing the older complacent generation of the IRB and replaced them with his younger passionate proteges.

The creation of the Irish Volunteers as a countermeasure to the UVF in 1913 and the outbreak of WW I in August 1914 presented Clarke with the opportunity he had worked all his life for. “England’s adversity would be Ireland’s opportunity” and on 9 September 1914 at the library of the Gaelic league at a meeting chaired by Clarke, it was decided to stage a rebellion in an effort to gain Ireland’s independence while England was preoccupied with the war on the continent.

The rebellion was scheduled for Easter week 1916. At 59 years of age Clarke was the oldest of the signatories; yet during the ensuing fighting at the GPO, Clarke seemed to be everywhere, impressing all with his cool demeanor and inspiring men a third of his age, a living symbol of the ideal they were fighting for. When after defying the British Empire the decision was made by Padraig Pearse to surrender rather than face increasing civilian casualties, Clarke broke down and wept.

Clarke had no delusions as to the fate that lay in store for him from a vengeful Britain. When the surrendering rebels were assembled, the British Officer commanding struck him across the face saying “This Old Bastard has been at it before!” and then proceeded to attempt to humiliate him by publicly stripping him. Realizing that his court martial was a pro forma performance, Clarke made no defense and was sentenced to be shot by firing squad. While many saw the Easter Rising as a failure, ironically Clarke, who had sacrificed so much of his life in the cause of Irish nationalism and could be forgiven for being bitterly disappointed that the Rising had not achieved an Irish Republic, remained confident. Tom Clarke, who learned the virtues of patience and persistence while in a British prison, saw the Rising in its true and bigger context. Among Clarke’s last words he noted: “I and my fellow signatories believe we have struck the first successful blow for Irish freedom. The next blow, which we have no doubt Ireland will strike, will win through. In this belief, we die happy.”

Clarke’s vision was prophetic, Ireland did strike “a next blow” and it partially “won through”; it is up to us today to see that Clarke’s vision is fully realized