Since the time of the Greeks, the myths and legends of heroes have followed a consistent pattern. The hero enjoys initial success and is catapulted to fame to only just as quickly have everything taken away from him and to fall from grace; then in the time of dire need the hero reemerges and asserts his nobility of character often by his personal sacrifice in the face of hopeless odds. Such is the story of Major John MacBride.

Since the time of the Greeks, the myths and legends of heroes have followed a consistent pattern. The hero enjoys initial success and is catapulted to fame to only just as quickly have everything taken away from him and to fall from grace; then in the time of dire need the hero reemerges and asserts his nobility of character often by his personal sacrifice in the face of hopeless odds. Such is the story of Major John MacBride.

John MacBride was born in Westport, County Mayo on 8 May 1868. John was educated by the Christian Brothers and later attended St. Malachy’s college in Belfast. MacBride then worked for some time as a draper before subsequently finding employment working for Hugh Moore and Company, a wholesale druggist and grocers in Dublin.

The quiet, uneventful life of a shop clerk was not for MacBride however. He had seen the reawakening of the call for Irish self-determination in the Land League movement of the late 1870s’s as his neighbors in Mayo fought to wrest control of Irish land from absentee Landlords and restore it to Irish tenant farmers. MacBride is also believed to have attended a ‘monster’ meeting in his hometown of Westport that was organized by the famous champion of Irish rights Charles Stewart Parnell. These events had a tremendous influence on MacBride who, at the age of 15, joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood; writing of the event later “I took an oath to do my best to establish a free and independent Irish Nation” . In 1891, MacBride as a member of the GAA was a member of the Honor Guard at Parnell’s funeral holding Hurleys draped in black cloth. As a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, MacBride traveled to Chicago to attend the Irish National Alliance convention. On his return he joked that he was “the most protected man in Ireland”, as British Detectives from the Intelligence branch tracked his every move.

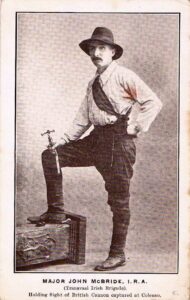

MacBride would soon be swept up in international events that would bring him to worldwide attention. In 1895, at the direction of the machiavellian British industrialist Cecile Rhodes, Dr Leander Starr Jameson led a raid by a group of 800 self described “policemen” (actually mercenaries hired by Rhodes) into the Transvaal area of south Africa allegedly to protect British interests from a nonexistent uprising; the real goal was to annex the newly discovered rich gold fields for Britain. The raid was a disaster when it was repulsed by the Boers (descendants of Dutch colonists who had occupied the land for nearly two centuries) leading to the Boer War. The outbreak of the war prompted MacBride to go to south Africa to organize the many Irish immigrants who were currently working in the gold fields to “strike a blow at England’s power abroad when we could not do so at home”. MacBride organized an Irish Brigade to fight with the Boers and was given the rank of Major. MacBride and his brigade soon won a reputation for bravery and international fame. Supporters in Dublin sent MacBride’s Brigade a green flag with a gold harp which MacBride treasured till his death; while fighting the British he was put up as a candidate for Parliament representing South Mayo (he lost).

However, the Boers could not indefinitely resist the full might of the British; and after a series of defeats their eventual surrender became inevitable. In an act of gratitude, the Boer government chartered a ship to transport the remaining members of the Irish Brigade, including MacBride, back to Europe. MacBride went to Paris; a celebrity but penniless. He soon became a member of the Irish cultural circle that frequented the city of lights including Yeats, Arthur Griffith and, most significantly, the legendary beauty, actress and committed Irish nationalist Maud Gonne. In need of Income, MacBride set out on a speaking tour of America. Not being a naturally gifted speaker he invited Gonne to accompany him and coach him on speaking to large audiences.

The speaking tour was a success and MacBride married Gonne. The marriage would produce a son, Sean MacBride who would later go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize. However, their shared love of Ireland was not enough to span the differences between the aristocratic and bohemian Gonne and the working class world worn MacBride. What followed was a nasty and bitter divorce in conjunction with a smear campaign orchestrated by W.B. Yates who was obsessed with Gonne and hated MacBride for succeeding in marrying her while she had rejected several proposals from him. His reputation damaged, MacBride returned to Dublin where he was reduced to taking a job as a water bailiff enforcing fishing regulations. While still passionate about nationalist causes, his notoriety with British authorities and the scandal of his divorce kept him an outsider in nationalist leadership.

On Monday, April 24, 1916 John MacBride was dressed in his best suit to meet his brother who was coming to Dublin to be married when he encountered a column of Irish Volunteers commanded by Thomas MacDonagh who were marching to occupy Jacob’s Biscuit Factory as part of the Easter Rising. Hearing that the Irish Republic had been proclaimed, the old soldier immediately forgot about old slights and the wedding and asked to join the column as he felt it was his duty. MacDonagh not only accepted, but immediately appointed MacBride second in command. While no doubt a curious sight as he marched with the uniformed volunteers in his blue formal suit with a walking stick and cigar; MacBride would prove invaluable over the next few days with his military knowledge and in steadying the men by his personal example. His leadership was invaluable when it came to the time of the surrender; many of MacDonagh’s men wanted to fight to the last, but MacBride stepped forward and asked them did they think he would surrender if there was anything fighting could achieve? MacBride’s statement had the desired effect and the men accepted surrender saving needless further loss of life.

MacBride was tried by British court martial and sentenced to death despite government instructions that only the signers of the Proclamation and principle Commanders were to be executed. While it was clear that MacBride was not in command at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory (they had already shot MacDonagh as the commander), both the Military Governor and President of the Court Martial were Boer War veterans who had battled MacBride’s Irish Brigade in Africa and this may have played in their decision.

MacBride was taken to the yard at Kilmainham Gaol on 5 May 1916 to be executed by firing squad. His last request was that he not be blindfolded, “You know I have looked down your rifles before, I am not afraid.” Perhaps the firing party was afraid to look him in the eye as the request was refused. John MacBride went to his death as only a hero could.