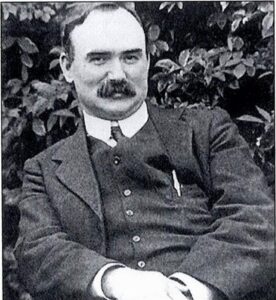

James Connolly was born in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1868. His parents were poor rural laborers from Monaghan that had traveled to the capital of Scotland in search of better opportunity only to settle in one of the city’s poorest sections, an Irish enclave in the Cowgate section nicknamed “Little Ireland”. Poverty was a constant childhood companion; forcing young Connolly to leave school at the age of ten and take work as a printer’s devil and then a baker’s assistant where he often worked 14 hour days.

James Connolly was born in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1868. His parents were poor rural laborers from Monaghan that had traveled to the capital of Scotland in search of better opportunity only to settle in one of the city’s poorest sections, an Irish enclave in the Cowgate section nicknamed “Little Ireland”. Poverty was a constant childhood companion; forcing young Connolly to leave school at the age of ten and take work as a printer’s devil and then a baker’s assistant where he often worked 14 hour days.

At fourteen, Connolly took the only opportunity Victorian Britain offered improvised young men like him for advancement; he joined the British Army. Under an assumed name and lying about his age, he joined the King’s Liverpool Regiment, not out of patriotism but for steady pay and regular meals. For the next six years he served with the regiment mainly in Ireland; employed in “aiding the civil authorities” in enforcing the repressive landlord system. Connolly was struck by the injustice of it all, an empire built and maintained by an army recruited from the poor being used to enforce laws that perpetuated poverty. In 1888 Connolly deserted the Army and returned to Scotland.

While serving in Ireland, Connolly had met Lillie Reynolds, a Protestant domestic servant from Wicklow whose family had fought in the 1798 rebellion, whom he married after returning to Scotland. While lacking formal education, Connolly was an avid reader and soon fell under the influence of the socialist thinking that was spreading throughout Britain. He joined the Scottish Socialist Federation (SFF) and rapidly became immersed in politics. He began writing and publishing articles for the SFF and soon rose to prominence in the organization, becoming the Secretary of the Edinburgh Branch and unsuccessfully running as the organization’s candidate in the 1894 municipal election.

However, Connolly’s political success was not mirrored in his private life. Connolly had a growing family of three daughters when he lost his job as a carter for the city of Edinburgh. His attempt to start his own cobbler’s business failed miserably. In 1896 he was offered the job as an organizer for the Socialist Club in Dublin for a £1 a week, beginning his association with the city for which his fate and memory would forever be entwined. Connolly went about his task with the passion and drive for which we was famous. He quickly organized the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP), to work for an independent socialist Ireland. In 1898, when many nationalist organizations were celebrating the centenary of the 1798 rebellion, Connolly took his fellow Nationalist to task writing they “must demonstrate to the people of Ireland that our nationalism is not merely a morbid idealising of the past, but is also capable of formulating a distinct and definite answer to the problems of the present”. Under Connolly the ISRP began publishing its own newspaper and started an influential campaign against Britain’s involvement in the Boer War that garnered widespread support throughout Ireland.

Yet, poverty remained a constant specter at the Connolly’s table; the small size of the ISRP meant that Connolly often went unpaid. Consideration for his family moved Connolly to immigrate to America in 1903. Traveling ahead of his family, he hoped to secure a position as a newspaper writer, but was forced instead to take a position as an insurance salesman in Troy, NY. Connolly found himself at odds with American Socialists as he rejected their belief that it was impossible to hold religious and socialist beliefs simultaneously. This dark period was compounded when Connolly reunited with his family only to learn that his oldest daughter had died just before sailing to America as a result of a tragic accident. The family relocated to Newark where Connolly was employed by the Singer Sewing Machine Company. Connolly soon became involved in the International Workers of the World (IWW). He became the IWW organizer in the Bronx; becoming fluent in Italian so he could address the large body of immigrant workers from Italy.

Yet, Connolly never forgot his dedication to Ireland. He wrote that “I have set my heart on getting back to Ireland. I feel that most anyone can do the work that I am doing here; but there is work to be done in Ireland that I can do better than most anyone. I am always dreaming of Ireland; dreaming of going back to the fight at home”. He returned to Dublin in 1910 to find the labor situation great changed. While land reform had greatly benefited rural Ireland, the increasing industrialization of Ireland had meant an equal increase of urban poverty. On Dublin’s Henrietta Street, there were 15 houses with 835 people living in one room tenements. Connolly became a member of Jim Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers Union, (ITGWU), which had reinvigorated trade unionism in Ireland. He quickly rose in the ITGWU and was arrested for his role in the Dublin Lockout of 1913, where members of the Royal Irish Constabulary baton charged protesting workers, killing two and injuring several hundred. With his release from prison and with Jim Larkin having left Ireland for America, Connolly took over the leadership of the ITGWU. As a result of the Lockout, the ITGWU formed a paramilitary unit, The Irish Citizen Army, to prevent striking workers from another attack as had occurred during the Lockout. Under Connolly’s command and trained by an Anglican retired British Army Captain Jack White it became a small but efficient military unit numbering approximately 300 with 28 women.

Connolly was enraged by the simultaneous betrayal by Britain to enforce the Third Home Rule and Britain’s entry into WW I which he viewed as the working class of several nations slaughtering each other for no higher purpose than a squabble between empires that had shown no interest in them. Connolly was in the midst of planning his own small scale insurrection using the Irish Citizen Army, when Pearse and MacDiarmada realizing that a premature action by Connolly would endanger their plans for the larger Rising. On 19th January 1916 Connolly was brought on as a member of the Military Council for the Rising. It was a marriage of convenience, as Connolly’s socialist views were not shared by others on the council, but they were in agreement that the first step was Ireland’s independence at which point the Irish people could then decide their own direction.

The ITGWU Headquarters, Liberty Hall, quickly became the epicenter of the rising. On Easter Sunday, the Proclamation of the Irish Republic was printed on the presses at Liberty Hall. Because of his Military experience and charisma Connolly had been appointed military commander of the Dublin forces. Coming down the stairs in the uniform of a Commandant of the Citizen Army, Connolly’s friend William O’Brien nervously asked him did he think they had a chance, to which with a half-smile the pragmatic Connolly responded “Bill, We are going out to be slaughtered”. Yet, Connolly knew that irrespective of the odds Irish men and women had to strike to maintain their claim for independence and he believed that no matter what action now would kick off a larger action. His leadership in the GPO was unequaled; Michael Collins said of Connolly that “I would have followed him through hell.” On the Thursday of the rebellion, Connolly personally led a party of men out of the GPO to occupy and construct a barricade at the offices of the Irish Independent. He received a wound to his arm, which he had secretly dressed, warning the person who treated him to say nothing. Returning to the barricade, he was struck by a snipers bullet in the ankle, shattering the bone and causing a great loss of blood. He was taken back to the GPO, where a captured British Army Doctor, Lieutenant Mahoney who was from Cork, treated his wounds. Despite being in excruciating pain, Connolly asked to be placed on a bed with casters so that he could be wheeled about the GPO; as Pearse wrote “(Connolly) lies wounded, but is still the guiding brain of our resistance”

That resistance came to an end as Connolly cosigned Pearse’s surrender order lest more civilian fall to British shelling. He was too ill to be taken to jail and was taken to the state apartments at Dublin Castle, which had been converted to a first-aid station for returning troops from WW I. He was court-martialed, and despite doctors saying he had only days to live, sentence to be executed. He was transferred by ambulance to Kilmainham Gaol. He was carried by stretcher to the site of execution, and unable to stand, was tied to a chair to be shot. Given absolution and last rites, the priest asked him to pray for the soldiers about to shoot him, Connolly said: “I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights.” The execution of Connolly drew such outrage, both in Ireland and the United States, that the British Prime Minister ordered the end of the executions.

When his wife visited Connolly shortly before his death, Connolly expressed the fear “They will all forget that I am an Irishman.” Let us vow that this never be the case; for while born in Scotland there are no greater Irishmen than James Connolly.

Neil F. Cosgrove, Historian