It has been said of those that fought at the battle of Iwo Jima that “Uncommon Valor was a Common Virtue.” It could also be said of many Irish American families that “Uncommon Virtue is a Common Value”. Both are illustrated in the story of William G. Walsh.

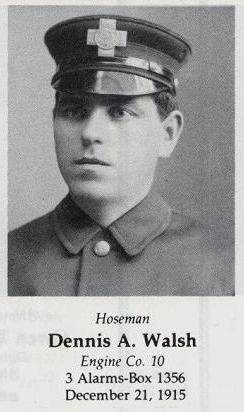

William G. Walsh was born on April 7, 1922, in Maine to a young mother who gave the child to her grandmother to raise. When the grandmother herself fell ill, she entrusted the baby to her friend Mary Walsh from Roxbury, Massachusetts. Mary, who had emigrated from Ireland in 1898, was no stranger to adversity. She had been married to Dennis Walsh, himself an Irish immigrant, who had been killed in a building collapse while fighting a fire as a Boston firefighter in 1915 just a few days before Christmas leaving her with two children and a third on the way. Mary Walsh provided for her family by working as a housekeeper, cook, waitress and by taking in borders, a model of Irish strength and grit. Despite her own struggles, she still took in the infant William and, when his grandmother died, adopted him.

Young William was quickly christened “Red” in the neighborhood due to his sandy red hair. He developed a reputation as both an athlete and a natural leader; in baseball, he was a catcher known for being able to manage his pitchers. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Sunday, December 7, 1941, he and his entire baseball team went to the closed Federal Building in Boston and slept outside on benches to be first in line when the recruiting office opened Monday morning.

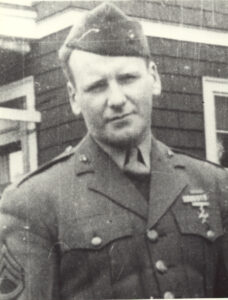

Enlisting in the Marines, William Walsh volunteered for the elite Marine Raiders and saw extensive service at Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Tarawa, and the Russell Islands. He was nominated for non-commissioned officers school, promoted to platoon sergeant and assigned to the G Company 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division, when his unit took part in the invasion of Iwo Jima.

On February 27, Walsh and his men were tasked to take a strategic ridge vital to the capture of Motoyama Airfield 2. Despite heavy shelling and bombing, as soon as the Marines moved forward, the Japanese defenders reoccupied defense which had been constructed to put any attacker in a murderous crossfire and was pre-sighted for artillery and mortars. Walsh’s unit was pinned. Realizing that to stay was to die, Walsh shouted, “Hell, we can’t stay here! Let’s hit them again!” Walsh’s Marines charged again only to be met with machine guns and grenades. Men began to scramble back, but Walsh had taken cover in a crater with some wounded men and refused to leave them. A Japanese grenade was thrown into the hole and Walsh without hesitation, threw himself on the grenade giving his life for his men. William Walsh was awarded the Medal of Honor.

However, this would not be the last medal presented to the Walsh family. Dennis Walsh, the child that Mary Walsh had been carrying when her husband was killed as a Boston firefighter, had joined the Franciscan Order taking the name Cormac. When the Korean War broke out, Fr. Cormac Walsh joined the U.S. Army as a chaplain, where he was awarded four Silver Stars and a Presidential Citation for his care of the wounded while under fire; he was the most decorated chaplain of the Korean War. After his career with the Army, Fr. Walsh served for eighteen years as the prison chaplain at the maximum-security Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora, New York. An inmate at the prison stated, “He created a legend of goodness and left us a legacy of love.“

In Boston, there is a memorial plaque with the name of Dennis Walsh’s inscribed for his sacrifice as a firefighter. In Dorchester, there is a park named for William Walsh, and there is a bridge named for Fr. Cormac Walsh. There should equally be a monument to Mary Walsh, who, like so many Irish women, silently lead a life of dedication and fortitude in the face of adversity while never losing her Christian Charity.

There are many, many stories like the Walsh’s; many of us have similar stories in our own families. We should remember them as we march on St. Patrick’s Day and make sure they are not lost by passing them onto the next generation.

Neil F. Cosgrove, Historian

Note that with deep regret and despite best efforts, I was unable to locate a photo of Mary Walsh.