With the advent of every spring and the approach of St. Patrick’s Day merchandise dealing in Irish Stereotypes and tropes bloom before the first crocus. Despite the fact that in our initiation oath, we pledge to “… not countenance by my presence or support any performance that may reasonably be interpreted as caricaturing or debasing the Irish people,” too many of us pass off these items as “a joke.” A review of the origin of these stereotypes shows that they are far from laughing matters.

Since the invasion of Ireland by Strongbow in 1170, a basic tenet of English colonial policy was not to merely to occupy the Irish land, but the Irish mind as well. From the Statutes of Kilkenny, English/British colonial policy sought to debase the proud heritage and history of the Irish people and create a sense of inferiority and dependency. Laws sought to eliminate the Irish language, ban Irish customs, dress, and sports. The greatest assault on the Irish mind was the Penal Laws, which sought not only to destroy the religious conscience of the Irish people but their final debasement through barring education. The British parliamentarian Edmund Burke accurately surmised the Penal Laws in Ireland as “a machine of wise and elaborate contrivance, as well fitted for the oppression, impoverishment, and degradation of a people and the debasement in them of human nature itself, as ever proceeded from the perverted ingenuity of man.”

When the Penal Laws and their overt oppression became politically unsustainable, a new “wise and elaborate contrivance” was introduced: “the Stereotype.”

However, Burke may have been premature, as when the Penal Laws and their overt oppression became politically unsustainable, a new “wise and elaborate contrivance” was introduced: “the Irish Stereotype.” “Irish Paddy ,” whom a foreign government had done everything in its power to degrade, was now to be depicted as not intelligent enough to govern himself; that is why he needed paternal British rule. “Paddy” was lazy, that is why he grew the potato, a crop that required little maintenance, not because the potato was the only viable crop that could provide sustenance on the smaller and smaller plots of land that English landlords were forcing the Irish onto.

These stereotypes came together to provide readymade excuses when a potato blight hit Ireland in September 1845 and famine ensued. See, it is all Paddy’s fault; sending aide and relief would only encourage his bad habits; the famine is the result of a moral defect in the Irish character, not our administration. Wasn’t it silly that the Irish were so reliant on the Potato (sadly, this last point is still echoed in more than a few school curricula today)? It is not an exaggeration that stereotypes led to the death of one million Irish men, women, and children.

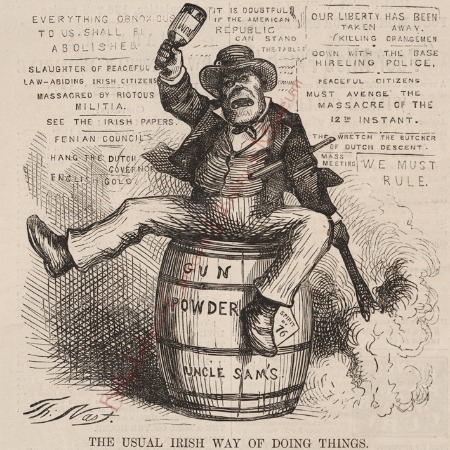

When thousands of Irish came to America’s shores to escape hunger and oppression, they, unfortunately, found that despite independence, more than a few Americans clung to their puritan English roots and prejudices. Again, “Paddy’s” problems were of his own devising. It was the time of Darwin’s theory of evolution, and clearly the Irish represented an earlier and more primitive stage of man; cartoons, and particularly those of Thomas Nast depicted the Irish as ape-men. Despite the irrefutable evidence of tens of thousands of Irish Americans who died in America’s Civil War, the loyalty of “Paddy” as a Catholic was still suspect, a charge that continued to be made during the campaigns of Al Smith, John F. Kennedy and even today in recent judicial nominations.

However, the most effective and persistent stereotype is that “Paddy” is a habitual drunk. As with any people of any ethnicity, there are those who overindulge and it is well established that the despair of poverty has historically exacerbated the issue among communities impacted, but this is a clear case of confirmation bias; of seeing proof to justify preexisting prejudices. It was once again an attempt, particularly by Protestant evangelicals, to point to the moral defects of the Irish character and their alien-ess. It was also an attempt to hinder a growing Irish American political identity and the nascent labor movement at which the Irish were at the center. The demonized Pub and “Grog House” was where the Irish met to discuss the issues of the day and organize, for the Irish the saloon served the same role as the salon for the social elite. John “Blackjack” Kehoe was falsely accused of being “The King of The Molly Maguires” and executed largely because he was a member of the AOH and owned a tavern where Irish miners met to discuss labor organization.

We may think that the impacts of negative stereotypes are confined to the past, but are there? What is the message being sent when (rightly) society condemns insult and ethnic-based stereotypes to other heritages, but tells the Irish to laugh at “Irish Today, Hung Over Tomorrow”? Is it not sending that same old message that our history and heritage are inferior and not worthy of protection? Certainly, some Irish clichés are worthy of no more than an eye-roll, but can we really say that about a “Drunk O’Meter” where the maximum red zone reading of intoxication is “Irish”? Despite being in the 21st century, are these items not sending the same 18th-century message, deflecting from the trials and triumphs of the Irish? Are these

Items really a laughing matter?

Neil F. Cosgrove, Historian

The great enemy of truth is very often not the lie– deliberate, contrived and dishonest–but the myth– persistent, persuasive and unrealistic. Too often we hold fast to the clichés of our forebears. We subject all facts to a prefabricated set of interpretations. We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.”

John F. Kennedy