Even today, our school children are told the story of the American Revolution as one of New England Puritan Yankees and “Scots-Irish riflemen” on the frontier fighting for freedom. Over time, this portrayal has hardened into a historical dogma. Even in an age of revisionism that rightly seeks to recover the voices of women, African Americans, and Native peoples, the Ulster Scots narrative remains untouchable. Those who challenge it and point to the central role played by the Gaelic Irish are treated as heretics. Yet the evidence is there, and it tells a very different story: Irish Catholics were not only present, they were indispensable.

For the Ancient Order of Hibernians, this isn’t just an academic oversight. Our mission is to preserve Irish Catholic heritage and defend the truth of our community’s history. If our forebears’ sacrifices are erased from America’s founding story, then the work of remembrance and advocacy falls to us.

Colonial America was no friend to Catholics. Every one of the thirteen colonies had penal laws on the books against them. Catholics were barred from holding office, priests were forbidden, and Catholic worship was restricted. Pennsylvania and Maryland were known to “turn a blind eye” and be laxer in enforcement, but the laws remained.

By the mid-1700s, Catholics are usually estimated at only 1–2% of the colonial population overall. But because Catholic priests and parishes were outlawed in much of the colonies, records of baptisms, marriages, and deaths were rarely kept. The actual number was almost certainly higher. What is clear is that Catholics were most visible in Maryland and Pennsylvania, where thousands formed recognized communities despite the odds.

That left few records for historians to consult. Later writers twisted this silence into “proof” that Catholics were absent. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Despite prejudice, some Catholics reached prominence. Charles Carroll of Carrollton was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration.

Stephen Moylan, born in Cork, served as quartermaster general and coined the phrase “United States of America.” He later became the first commander of the Continental Light Dragoons, establishing America’s cavalry arm and leading it with distinction.

Commodore John Barry, from Wexford, became the most successful American naval commander of the war, capturing more than twenty British ships and fighting the Revolution’s final naval battle in 1783. His record eclipsed John Paul Jones—but Barry’s Catholicism meant he was sidelined in memory.

These names prove that Catholics were not absent. But the real Catholic story is in the ranks.

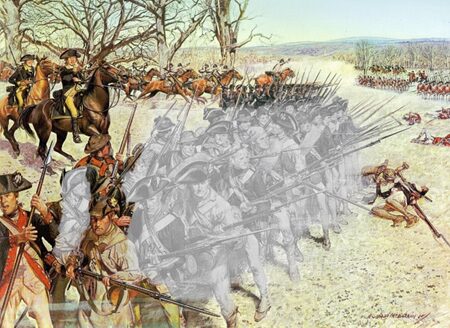

Pennsylvania’s Continental regiments were so heavily Irish that General Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee said they “might more properly be called the Line of Ireland.” Muster rolls burst with Murphys, O’Neills, and Kellys.

No one can pin down the exact number of Irish-born in the Continental Army—muster rolls rarely note birthplace or religion. But the consensus is clear: the Irish were the largest group of foreign-born soldiers. Estimates range from a quarter to nearly half of Washington’s army at various points. Even the lowest figure is significant.

And Britain noticed.

In 1778, British commander-in-chief General Sir Henry Clinton wrote that Washington’s army was “full of Irish.” In Loyalist New York, the Royal Gazette sneered that his troops were “an Irish rabble, more fit for the shillelagh than the musket.” And in 1783, in the Irish Parliament, Lord Mountjoy declared: “America was lost by the Irish… I have been assured on the best authority that the Irish language was as commonly spoken in the American ranks as English.”

These were not Irish boasts—they were British laments. Mountjoy’s remark describes Gaelic Catholic emigrants, not “Ulster Scots”. Britain acknowledged what America conveniently forgot: the Irish were not marginal; they were central to the struggle for independence.

No story shows the distortion better than that of Timothy Murphy, the legendary rifleman at Saratoga. As a sniper, Murphy killed Sir Francis Clerke and General Simon Fraser, throwing the British into disarray at a decisive moment. His parents were from Donegal—then, as now, overwhelmingly Catholic and Gaelic. Even his name is telling: Timothy comes from Tadhg, a name so associated with Irish Catholics that Ulster Scots Protestants used it as a slur for their Catholic neighbors. Even today is some sections of Northern Ireland and Scotland an Irish Catholic is called a “Tim.”

Yet 19th-century writers confidently rebranded Murphy as “Scots-Irish.” Why? Because there are no Catholic parish records for his family. But Catholic priests and parishes were outlawed in colonial New York, so baptismal and marriage records were often never kept. Later historians twisted this silence into “proof” that Murphy couldn’t have been Catholic.

This is the double standard: when records are silent, Protestant identity is assumed; Catholic identity requires extraordinary documentation. Apply the same rule consistently, and Murphy’s Donegal origins, Catholic name, and historical context make him far more likely Catholic Irish than Protestant.

The erasure wasn’t limited to men. The most famous woman of the Revolution, remembered as “Molly Pitcher,” has long been identified as Mary Ludwig Hays, a German-American. Yet contemporary evidence says otherwise.

Eyewitness Joseph Plumb Martin saw her serve at a cannon in 1778. Her husband, William Hays, was an artillery gunner born in Ireland. In 1822, Pennsylvania granted Mary a pension in her own right for exceptional service at Monmouth. Carlisle neighbors remembered her Irish brogue and consistently described her as “an old Irish woman”.

The German version originates from a 19th-century historian’s mistake, which involved conflating the wrong Hays family and regiment. It is preserved in monuments and textbooks. The Irish heroine was recast as German.

The case of “Irish Molly” rests on eyewitness testimony, a state pension record, and the recollections of neighbors — all primary sources. By the standards of historical method, this is stronger evidence than a 19th-century historian’s record search that mistakenly attached the wrong Hays family and regiment.

These cases show how historical bias works. Pitcher’s German identity rests on a 19th-century historian’s mistake, yet it’s accepted without question. Her Irish identity has eyewitness testimony, pension records, and neighbors who remembered her brogue and clothing—yet it’s dismissed as speculation. The rules only work one way: mental gymnastics are accepted as proof of any other identity, while Catholic identity must be proven beyond doubt.

So why is this?

During the Revolution, Catholics were accepted out of necessity. Washington needed troops; Congress needed French Catholic allies. After victory, however, America’s ruling class rewrote the story. As Catholic immigration swelled in the 19th century, anti-Catholic prejudice hardened. To preserve a Protestant founding myth, Catholic contributions were recast: Timothy Murphy became “Scots-Irish,” Molly Pitcher became German, and John Paul Jones eclipsed Barry.

The erasure was not accidental. It was deliberate cultural editing, turning Catholic sacrifice into Protestant memory.

The record is clear. Barry captured more prizes than John Paul Jones. Moylan coined “the United States of America” and founded the Continental Dragoons. Carroll signed the Declaration. Murphy and Molly stood at Saratoga and Monmouth. Thousands of Irish privates filled the Pennsylvania Line.

Yet in American memory, Catholics were airbrushed out—because 19th century prejudice demanded a Protestant origin story. Correcting this is not about pride; it’s about truth. And it falls squarely within the mission of the Ancient Order of Hibernians: to preserve our heritage, to honor our ancestors, and to ensure that future generations know the whole story.

Britain realized that America was lost by the Irish. It is time America remembered they won it.