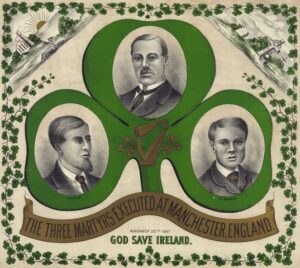

The morning of November 23, 1867, was cold and damp in Manchester. Three young Irishmen stood on a scaffold outside Salford Gaol before a crowd of ten thousand. William Philip Allen was nineteen, a carpenter. Michael Larkin, thirty-two, a tailor with a wife and five children waiting at home. Michael O’Brien, a shop assistant and U.S. citizen who had fought in America’s Civil War. Allen and O’Brien were from County Cork; Larkin from what was then known as King’s County (Offaly).

“I am dying for Ireland, dying for the land that gave me my birth,” Allen had written hours before. As he stood on the scaffold that Saturday morning, he could smell fresh-cut wood in the air—the material from which he made a living now fashioned into the instrument of his death. What he couldn’t have known was that his execution would become a rallying cry for Irish freedom.

The Rescue on Hyde Road

Two months earlier, on September 18, 1867, armed men ambushed a police van on Hyde Road in Manchester, freeing two imprisoned Fenian leaders: Colonel Thomas J. Kelly and Captain Timothy Deasy, both Irish-American Civil War veterans and Ancient Order of Hibernians members.

The Context

Kelly and Deasy had come to Manchester following the failed March 1867 rising in Ireland. At a secret convention in late June, three hundred Fenian delegates confirmed Kelly’s leadership as Chief Executive of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The two men remained in Manchester to reorganize and raise morale among Fenian groups in Britain.

On September 11, after leaving a nocturnal meeting in Oak Street, they were arrested by police who suspected them of planning to rob a shop. Found with loaded revolvers, they were initially charged with loitering under the Vagrancy Act—essentially a holding charge. Only after being identified, allegedly by an informer, were they charged with involvement in the Fenian Rising.

A Tragic Accident

The rescue achieved its objective. Kelly and Deasy escaped to America, never to be recaptured despite a £300 reward. But the cost was terrible.

The attackers had first called on the police guard inside to surrender and open the van. Police Sergeant Charles Brett refused, saying, “I dare not. I must do my duty”—words that would later be inscribed on his gravestone. When the police officer would not surrender, the attackers attempted to force the lock with tools. Only as a final resort did someone fire a shot at the lock to force it open.

At that precise moment, Brett, curious as to why the banging of tools had stopped, chose to look through the lock’s keyhole. The bullet passed through his eye and killed him instantly.

Anti-Irish Fury

Brett’s death—the first Manchester police officer killed in the line of duty—ignited anti-Irish fury. Queen Victoria herself wrote that “The Irish are really shocking, abominable people, not like any other civilised nation.”

Police raided Irish districts, arresting twenty-nine men for the crime of being Irish. It didn’t matter that no one knew who fired the fatal shot, or that Brett’s death appeared to be a tragic accident rather than deliberate murder. Someone would have to pay.

The Trial: “A Climate of Anti-Irish Hysteria”

The trial, beginning October 28, 1867, took place in what Reynold’s Newspaper described as “a climate of anti-Irish hysteria,” calling the proceedings “a deep and everlasting disgrace to the English government.”

Dubious Evidence

The evidence, other than the fact that the accused were Irish, was sparse and dubious. As Allen himself protested from the dock, many witnesses were “prostitutes off the streets of Manchester, fellows out of work, convicted felons.” Rather than proper identification parades, suspects were identified sitting in police custody, handcuffed and manacled—a practice Solicitor’s Journal later called “reckless swearing.”

A Lawyer’s Protest

Defense lawyer Ernest Jones, the Chartist leader who had himself spent two years in prison for seditious speeches, clashed with the court almost immediately.

“It appears to be discreditable to the administration of justice that men whom the law presumes to be innocent should be brought into Court handcuffed together like a couple of hounds,” he objected.

When the magistrate refused to remove the handcuffs, Jones “marched dramatically” out of the courtroom, declaring he could not “disgrace the Bar by proceeding with the defence.”

“God Save Ireland!”

Of five men initially sentenced to death, two were spared:

- Thomas Maguire, a Royal Marine on leave, was so clearly innocent that journalists covering the trial petitioned for his release.

- Edward Condon, an American citizen and Civil War veteran, received his reprieve at the eleventh hour when American ambassador Charles Francis Adams Sr. intervened, convincing British authorities to commute his death sentence to life imprisonment.

But when Condon was asked if he had anything to say before sentencing, he rose and delivered words that would echo through Irish history:

“I have nothing to regret, to retract, or take back. I can only say, ‘God Save Ireland!'”

The courtroom erupted. Supporters in the gallery took up the cry “God Save Ireland!”

No Mercy for Three

O’Brien, also an American citizen who had petitioned Ambassador Adams, received no mercy. Neither did Larkin or Allen. Despite weak evidence and none being accused of firing the fatal shot, they would die under a “joint enterprise” conviction.

From the dock, Allen declared: “I will die proudly and triumphantly in defence of republican principles and the liberty of an oppressed and enslaved people.”

O’Brien, asserting his American citizenship, spoke eloquently of British hypocrisy: “How beautifully the aristocrats of England moralise on the despotism of the rulers of Italy… but why don’t those persons who pretend such virtuous indignation look at home?” He concluded: “I positively say, in the presence of the Almighty and ever-living God, that I am innocent.”

Irish historian F.S.L. Lyons assessed it bluntly: the men were convicted “after an unsatisfactory trial, and on evidence that, to say the least, was dubious.”

A Botched Execution

The execution itself was horrific. Hangman William Calcraft’s incompetence meant Larkin and O’Brien strangled slowly. The drop having failed to kill Larkin, Calcraft jumped on his back to finish the job. Only the intervention of prison chaplain Father Gadd spared O’Brien the same fate. For forty-five agonizing minutes, O’Brien hung twitching while Father Gadd knelt before him, holding a crucifix before the condemned man’s face.

The brutality shocked even those who had demanded vengeance, amplifying the martyrdom that would follow.

Creating Martyrs

Frederick Engels immediately grasped the significance. The British government, he wrote to Karl Marx, had “accomplished the final act of separation between England and Ireland.” The Fenians had lacked martyrs. “They have been provided with these.”

Within days, funeral processions drew sixty thousand in Dublin alone. Condon’s courtroom cry, “God Save Ireland!”, became the refrain of a song set to an American Civil War tune by T.D. Sullivan, which served as Ireland’s unofficial national anthem until 1926. The lyrics captured the moment:

“High upon the gallows tree swung the noble-hearted three / By the vengeful tyrant stricken in their bloom / But they met him face to face, with the courage of their race / And they went with souls undaunted to their doom.”

The Legacy

The three became proof that Britain’s justice system, when applied to Irish patriots, was neither just nor impartial. The methods used—dubious witnesses, improper procedures, and predetermined outcomes—would become grimly familiar during Northern Ireland’s Troubles.

For anyone who identifies as Irish, their memory is both a reminder of past injustice and a call to continued vigilance. The struggle for truth and accountability isn’t a relic of the past. It’s the living legacy of three young men who died believing history would vindicate them, and of countless others who followed, refusing to let power write the final word on justice.