One can be forgiven for seeing Ireland’s march to reassert its independence as a sovereign nation as a series of rebellions and battles. However, perhaps Ireland’s greatest revolutionary act took place not on the battlefield but at the ballot box. It was the Irish General Election of 1918 and the subsequent establishment of Dáil Éireann (the “Assembly of Ireland”).

The Irish General Election was part of the broader United Kingdom General Election of 1918. The election occurred on December 14th, little more than a month after the end of WW I; the war which Britain allegedly fought that “small nations might be free”. It was the first election where there was universal suffrage for all males over 21 and all women over 30 (Britain had lost so many young men in the war Whitehall was afraid that the women’s vote would swamp the election if the requirements were the same). The combination of working-class men and women as a group who had previously never qualified to vote increased the Irish electorate from 700,000 to over 2,000,000.

Attitudes and loyalties had also changed in Ireland since the previous General Election of 1910. The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) which had dominated Irish politics since the time of Parnell had fallen out of favor over its failure to deliver Home Rule and its support for the British war effort. Coinciding with the IPP’s fall was the rise of Sinn Féin which had surged in popularity due to their identification with the Rising of 1916 and anger over the executions of the leaders of the Easter rising.

Most importantly, there was the “Conscription Crisis”. In March 1918, the German Army launched a major offensive which threatened to overwhelm the depleted ranks of the British Army on the Western Front. Compulsory military service was already in practice in the UK except for Ireland. While his party supported the war effort, the IPP leader John Redmond had warned that conscription in Ireland would be met with resistance. Redmond was right.

Prime Minister David Lloyd George attempted to introduce conscription to Ireland in April 1918. He further inflamed the situation by retroactively making Irish conscription a condition for Irish Home Rule (which had been signed into law in 1914 but suspended due to the war). Many saw this new condition as extortion. Lloyd George was nicknamed “the Welsh Wizard” and in this case with a stroke of his pen, he had accomplished something many thought impossible: he had united Sinn Féin, the IPP, the All Ireland League, the Labor Party, trade unions and the Catholic Church in common cause. His government further inflamed public opinion with the mass internment of 150 leaders of Sinn Féin over a manufactured “German Plot” which was nothing more than a ploy to intimidate those who opposed conscription and a propaganda move to drive a wedge between Ireland and its supporters in the United States. While British conscription was never successfully implemented in Ireland, the Irish electorate would not forget Britain’s tactics.

I am returned to Dublin pledged by the electors of North Roscommon to recognize no foreign authority, to maintain the rights of Ireland to independence and to initiate Ireland’s work of taking control of her own affairs.

The other key factor in the 1918 elections was Sinn Féin’s commitment to “abstentionism”; candidates elected would not take their seats in the British Parliament, but in a new Irish Government. Precedent for this policy had been established by Count Plunkett, the father of the executed 1916 leader Joseph Plunkett. When elected on February 3, 1917, Count Plunkett stated, “I am returned to Dublin pledged by the electors of North Roscommon to recognize no foreign authority, to maintain the rights of Ireland to independence and to initiate Ireland’s work of taking control of her own affairs.”

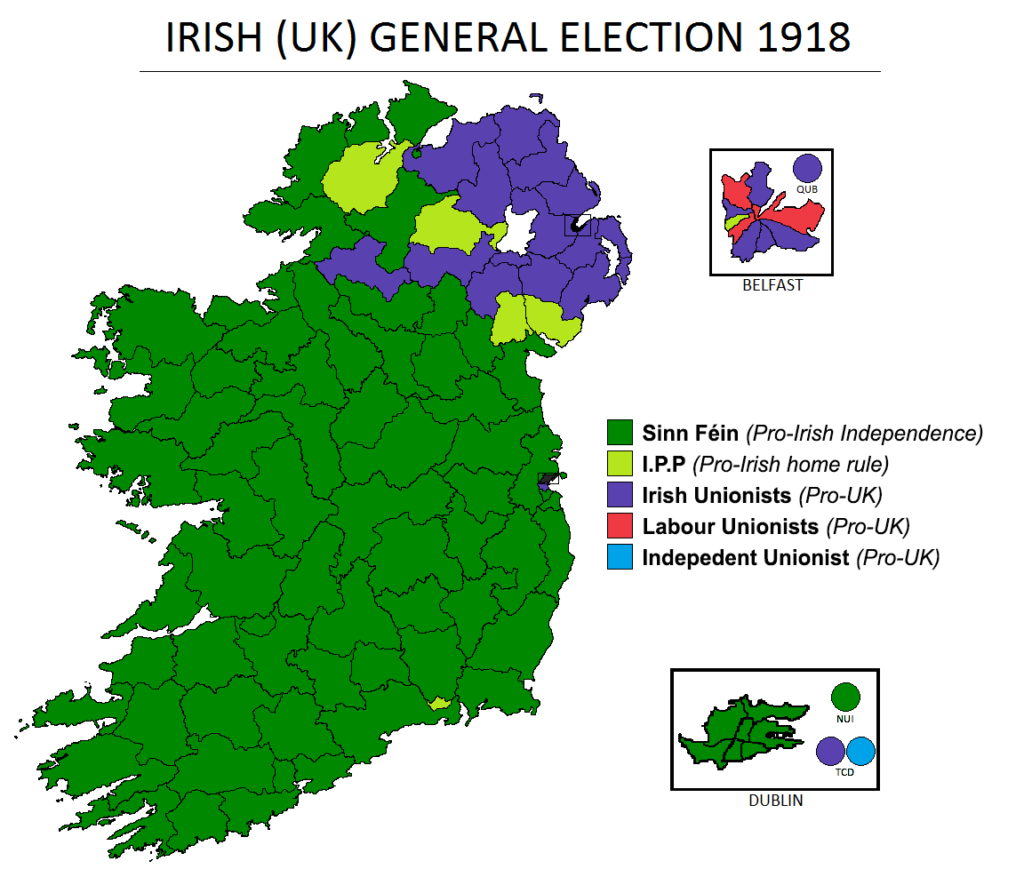

The choice in the 1918 election was clear: to vote for a Member of Parliament (MP) who would continue to sit in Westminster as part of a continuing association with the United Kingdom or to vote for a Sinn Féin Teachta Dála (TD) who would sit in an Irish assembly and was committed to press for self-determination for Ireland as defined in President Wilson’s Fourteen Points. The election results were just as clear; Sinn Féin, and a mandate for a sovereign, all-Ireland independent republic, secured 73 out of 105 seats.

It was a revolution carried out in the most peaceful means. Yet, despite the clear, democratically expressed will of the Irish people the British administration and unionists refused to recognize the Dáil. Representatives of the Irish people also soon found that President Wilson’s grandiose talk of “self-determination” did not apply if you were a captive colony of one of the WW I allies.

It was a squandered opportunity to resolve the “Irish Question fairly”. Having tried the ballot box again only to be met with cynical hypocrisy again, it was clear that Irish independence would have to be wrested by force. The result would be the start of the Irish War of Independence and nearly a century of violence in Ireland. Lloyd George and President Wilson would learn what would be articulated a half century later by an Irish American President, John F. Kennedy:

“Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”