In June 1866, a battle-hardened group of Irish-American Civil War veterans embarked on a daring mission: to invade British-controlled Canada and use it as leverage to secure Ireland’s independence. The group of Irish veterans had christened themselves “The Irish Republican Army” (IRA), the first time that name would enter the lexicon of the Irish-British conflict. This was the first in a series of incursions known as the Fenian Raids, which would occur between 1866 and 1871.

The invasion was organized by the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish American organization dedicated to Irish independence. They drew their name from the Fianna, the legendary warriors of ancient Ireland. The Fenians in North America were an extension of Ireland’s Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and mustered 125,000 members, many recent veterans of America’s bloodiest conflict, ready to fight for Ireland’s liberation.

No one was more emblematic of how committed and capable the Fenian force was than their commanding officer. Their chief strategist was Thomas “Fighting Tom” Sweeny. A famine-era immigrant from Cork, Sweeny had fought in the Mexican War and was wounded in the groin at the Battle of Cerro Gordo and lost his right arm at the Battle of Churubusco. While this may have ended the military career of most men, Sweeny stayed with the army and fought with distinction in the American Civil War, attaining the rank of Brigadier General.

It also appeared that the Fenians had support from the U.S. government. President Andrew Johnson thought that the Fenian activities could serve his political interests. The Johnson government was seeking reparations from Britain for its support of the Confederacy during the American Civil War, particularly the damages inflicted by the Confederate raider CSS Alabama, which had been built in England and was highly successful in praying on U.S. shipping, resulting in hundreds of millions of dollars in losses. There was also a strong sentiment for revenge in the administration for Canada being a safe haven for the Confederate Secret Service and a base where the Confederacy had launched raids into the United States, including the raid into St. Albans, Vermont, where Confederate soldiers robbed three banks and attempted to burn the town.

The Johnson administration, including Secretary of State William Seward, was reported to have tacitly approved of the Fenian plans, allowing the Brotherhood to arm and organize within U.S. borders. The support was part of a broader political game between the U.S. and Britain. Johnson was prepared to “recognize the accomplished facts” should the Fenians successfully establish a foothold in Canada.

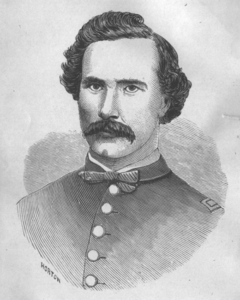

Colonel John O’Neill commanded the actual raid. Born in Monaghan and having witnessed the devastating effects of the Great Hunger, he had grown up on tales of resistance by his O’Neill ancestors. O’Neill was driven by a fierce desire to strike back at British imperialism. O’Neill had declared, “The governing passion of my life apart from my duty to my God is to be at the head of an Irish Army battling against England for Ireland’s rights.” When his men assembled, he boldly proclaimed, “Wherever the English flag and English soldiers are found, Irishmen have a right to attack.”

On June 1, 1866, led by John O’Neill, the Fenians executed their plan. Approximately 800 men crossed the Niagara River into Ontario, engaging in what would become known as the Battle of Ridgeway. Against a far larger but less experienced Canadian militia, the Fenians, leveraging their Civil War combat experience, secured a victory. It was the first military victory by Irish forces against imperial Britain in half a century. The initial success showcased Fenian military capability and audacity but was not enough to sustain a prolonged campaign.

Despite their initial success at Ridgeway, the broader Fenian strategy began to unravel due to logistical issues and dramatically shifting political support. As British and Canadian forces mobilized in response, the political climate in the United States took a decisive turn against the Fenians. As diplomatic pressures mounted and the prospect of a favorable settlement of the Alabama claims became feasible, Johnson’s administration shifted its stance. It now moved to prevent any further escalation that could jeopardize these negotiations. Consequently, the U.S. government now strictly enforced neutrality laws, effectively cutting off critical support to the Fenians.

At a crucial juncture, Johnson blocked the movement of approximately 4,500 Fenian reinforcements who were poised to cross into Canada to support O’Neill’s forces. Had it joined O’Neill, this significant force might have sustained the campaign longer and with greater military effectiveness. The prevention of these reinforcements left O’Neill’s men isolated and significantly under-resourced.

Ironically, the Fenian raids did directly lead to the formation of a new country: Canada. In Canada, the threat of these invasions contributed to the movement toward Confederation and strengthened national defense. The Fenians would try to invade Canada again, but the opportunity had passed. For Irish nationalists, the raids underscored the persistent struggle for Irish independence and put Britain on notice that “Ireland’s exile children in America” had not forgotten Ireland.

Sadly, few events are more subject to poor and misleading history than the Fenian invasions. Far too often, Historians present the topic to their audience for a laugh through a stereotypical lens as a “whisky-fueled” delusion. They omit pertinent facts, such as Canada at that time being only the provinces of today’s Ontario and Quebec, the disparity in the leadership and training of the forces, and the difficulties and expenses Britain would incur if they needed to launch a military response. We owe it to these men to remember and tell the real story.