Amidst the current debate on the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union, Brexit, there has been much talk about the “Union.” Measures that would prevent the return of a hard border in Ireland have been decried by loyalists as “undemocratic” and a threat to the “Union.” However, there was very little of democracy in the formation of the “Union” and from its inception its legacy has not been a unity of equality but of a shotgun marriage of domination.

The Norman conquest of Ireland displaced the governance of Ireland under Brehon law, a judicial system far in advance of its time where the rights of women were recognized, and every life under law had value, with the “Lordship of Ireland,” bound under feudal loyalty to the King of England. As in England, a parliament evolved out of the Great Council summoned by the King’s viceroy. However, as the “King’s men” assimilated to Ireland, some of the more powerful families began to identify more with their own Irish interests than those of a distant and foreign Crown. To check the power of the great families and any move toward Irish self-determination, “Poynings’ Law” was passed in 1494. Under “Poynings’ Law,” proposed legislation had to be sent to England for approval and possible amendment first before it could be introduced and voted on in Ireland. “Poynings’ Law” made the parliament of Ireland little more than a subcommittee of the English parliament.

As the centuries passed, the “Irish Parliament” became more and more exclusionary. The Tudor and Cromwellian conquests and the introduction of Penal Laws barred Catholics from the public sphere and curtailed the rights of “dissenters” (Presbyterians). By the 18th century, the “Irish Parliament” was an exclusive club of the Anglican landed gentry. However, even amongst the Crown staunchest supporters, cracks began to show in the Anglo-Irish relationship over the most fundamental interest: money. The 1700s saw both an expansion of English commerce and a series of laws emanating out of Westminster promoting British industry at the expense of Irish (similar laws also impacting the American Colonies would be one of the prime causes of the American Revolution). The 1649 “Woollen [sic] Act” expressly prohibited the export of Irish woolen materials to protect the British Wool industry. Ironically, this stimulated what would soon become the hallmark linen industry of Ulster, which in turn faced additional legislation to protect the British linen trade at the expense of Irish. Even the vested interests of the Protestant Ascendancy were beginning to chafe under the treatment of the alleged “Kingdom of Ireland” as a mere colony.

Events in the late-1700’s would provide Ireland’s opportunity in England’s adversity. The entry of England’s old adversaries France and Spain into the

American Revolution had transformed that conflict into a world war and stretched British military capability to the breaking point. There were fears that Ireland could be a target for invasion. An “Irish Patriot Party” was formed by Henry Flood and Henry Grattan, which raised an armed militia, purportedly to repel any attempts at invasion, but which gave the Irish Parliament what was in effect its own army to enforce its demands. Calls for legislative independence for Ireland made at the Irish Volunteer Convention at Dungannon in 1782 sent a clear message to the British government. On 16 April 1782, Grattan passed through the ranks of Volunteers drawn up outside the parliament house to move a declaration of the independence of the Irish parliament to which the British government had no alternative but to concede.

However, “Grattan’s parliament” was not a tide lifting all boats, nor a landmark in political reform. Catholics and Presbyterians were still not represented in Grattan’s “Irish Nation.” Legislative reform was stifled by Britain controlling the Irish parliament through patronage and graft. Frustrated by the lack of progress and inspired by the American and French revolutions, the United Irishmen composed of Catholics and Protestants rose in violent rebellion in 1798, a revolt that Britain brutally suppressed.

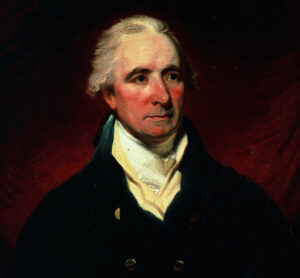

“My occupation is now of the most unpleasant nature, negotiating and jobbing with the most corrupt people under heaven…“

Viceroy Castlereagh, the Chief Secretary for Ireland

Simultaneously, England was once again at war with France, and this time France had indeed attempted two invasions of Ireland. The British government believed they could not continue to afford (and given the cost of patronage and graft doled out to ensure the Irish parliament’s alignment to British ends this was quite literal) any ambiguity in the relationship between Britain and Ireland. The British Government began a campaign for an “Act of Union” wherein the Irish parliament would be eliminated, and Ireland would be governed from Westminster. Bribes, honors, and peerages flowed from London to convince the members of the Irish parliament to vote themselves out of existence. Throughout the year 1799, the government of Prime Minister Pitt employed graft and corruption on a massive scale. Even Viceroy Castlereagh, the Chief Secretary for Ireland became so sickened by his own government’s tactics that he wrote “my occupation is now of the most unpleasant nature, negotiating and jobbing with the most corrupt people under heaven…I despise and hate myself every hour for engaging in such dirty work.” The home office’s secret service accounts from the period indicate that over £30,000 was distributed in the form of illegal bribes.

However, the “dirty work” had the desired effect, the Irish Parliament voted for Union and the dissolution for even minimalist Irish home rule. On 15 January 1800, the Irish Parliament sat for the last time; on January 1, 1801, Ireland entered the Union of “Great Britain and Ireland.”

“We obtained that union against the sense of every class of the community, by wholesale bribery and unblushing intimidation.”

British Prime Minister William Gladstone

The consequence of the Act of Union for Ireland was far-ranging, with devastation extending far beyond politics. Ireland’s representation by 100 seats out of a total of 658 in the House of Commons was little more than a lobbying group. The closure of the Irish parliament meant Dublin was no longer a thriving center of politics and culture; the talented and ambitious soon left for London, leaving the city to slump into decay. Absentee landlordism increased, and the divide between the ruling Ascendancy and the people of Ireland widened, the disastrous consequence of this disassociation would come to fruition during the Great Hunger.

British Prime Minister William Gladstone said of the Act of Union, “There is no blacker or fouler transaction in the history of man. We used the whole civil government of Ireland as an engine of wholesale corruption . . . we obtained that union against the sense of every class of the community, by wholesale bribery and unblushing intimidation.” The remnants of the Act of Union, Northern Ireland, as itself been no stranger to “wholesale bribery and unblushing intimidation” in recent years. Let us hope that the day is soon coming when this inequitable Union is dissolved, and Ireland will be whole and free.

Neil F. Cosgrove, Historian