January 30, 1972, was an uncharacteristically bright and sunny day for an Irish winter in Derry, Northern Ireland. It was the day of a planned peaceful protest march against the policy of internment without trial instituted by the British Army; a policy that, while allegedly created to curtail sectarian violence, was itself hypocritically sectarian in its targeting of Catholics. One of the march’s participants, Eamonn McCann, recalled: “There wasn’t a cloud in the sky.” Despite the grim subject of the protest, he said the atmosphere was “almost carnival-like” as family and friends walked together in a rare break from the usual winter gloom. Yet, before the sun would set on that day, it would become one of the most infamous in Irish history, a day that half a century on still casts a dark shadow on the present and has come down through history as ‘Bloody Sunday.’

Like many turning points in history, ‘Bloody Sunday” was the product of years of prior events. Fifty years earlier, Northern Ireland had been carved out of Ireland to create a “A Protestant Parliament for a Protestant people“; an ironic reward for Unionists who had threatened ten years earlier to demonstrate their loyalty to the Crown by armed insurrection against the constitutionally passed Home Rule Act which would have given all the people of Ireland a parliament is which their voice could be heard. From its inception, Northern Ireland was a state founded on prejudice and hypocrisy.

Nowhere was that prejudice and hypocrisy more evident nor keenly felt than in the city of Derry. Although Catholics made up 60% of Derry’s population, election wards were drawn to ensure Unionists maintained an iron-handed control of the local government. Even worse, the basic human necessity of housing had been turned into a tool of political power. Despite being abolished in the rest of Great Britain in 1945, Northern Ireland still maintained a requirement that only property owners or leaseholders and their spouses were permitted to vote, and the Unionist Government controlled the housing stock. Instead of improving or adding additional housing to Derry, the Government directed resources to develop a ‘new town’ called Craigavon (named after a prominent Unionist) in a Unionist area. When it was decided to build a second University for Northern Ireland, the sleepy unionist seaside town of Coleraine was chosen despite Derry being the North’s second-biggest city with four times the population. There was widespread discrimination in employment targeting Catholics.

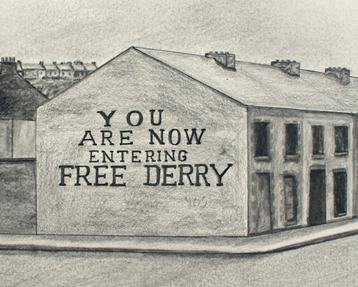

Taking inspiration from America’s own Civil Rights movement, Civil Rights associations and protests began to form in Northern Ireland. While the initial protests were peaceful, they were met with widespread violence with members of the Police Force, an exclusive Unionist franchise, becoming partisan combatants rather than protectors of law and order. In January 1969, a Civil Rights march was attacked by off-duty Ulster Special Constabulary (B-Specials) members and other Ulster loyalists during the Burntollet bridge incident. The RUC refused to protect the marchers and joined the attackers in many instances. That night, members of the RUC broke into homes in Derry’s Catholic Bogside area and assaulted several residents. Under attack from the very forces sworn to maintain the peace, the community set up barricades and organized citizens patrols. On the gabled wall of a home at the corner of Columbs Street was painted “You are now entering Free Derry” declaring the area an autonomous zone.

The situation continued to descend into anarchy. In August 1969, there was the “Battle of the Bogside” during the annual Unionist Apprentice Boys March, a conflict sparked when Loyalist participants threw pennies from the walls of the city at residents in the Bogside. Over the next two days, 1,000 people were injured in the rioting in Derry. The violence quickly spread; in Belfast, a Loyalist mob burned all the Catholic homes along Bombay street, leaving some 1,800 people homeless.

Having been derelict as the cycle of violence escalated in Northern Ireland, the British Government, now fearing the collapse of the Northern Irish Government, sent the British Army in to restore law and order. They were initially welcomed by the Catholic Nationalist population, who believed they would be impartial. However, they soon realized that restoring “law and order” also meant preserving the discriminatory status quo, and relations soon deteriorated, and violent confrontations began. The British Army implemented the policy of internment of Catholics that was the motivation for the protest march on Bloody Sunday.

The protest march had intended to make their way to the Derry city center and Guildhall, where there would be a series of speeches. They found the route blocked by British Army Barricades as they approached the city center. The organizers decide to reroute the march to “Free Derry” corner. However, some youths broke away and began throwing stones at the soldiers at the barricades. The soldiers responded with water cannons, rubber bullets, and CS gas. Sadly these clashes had become familiar, and observers reported it was not intense and was subsiding.

Unfortunately, the violence subsiding was not convenient for Major General Robert Ford, Commander of Land Forces in Northern Ireland. Appointed in August of that year, he was frustrated with the British Government’s official policy of restraint that the existence of “Free Derry” symbolized. In a memo dated 7 January, Ford had written to his superiors of “coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ringleaders amongst the DYH (Derry Young Hooligans), after clear warnings have been issued.” Ford had specifically come to Derry on that day to teach the Nationalists a lesson with plans for a mass arrest operation called “Operation Forecast,” ignoring the risk that such an operation being conducted amidst a large demonstration would risk innocent lives.

Bypassing the local commanders in Derry, Ford brought with him his own hand-picked unit to execute the operation: the 1st Paratroop Regiment from Belfast. 1st Para prided themselves on being the toughest regiment in the British Army. In August, the regiment had already earned an infamous reputation for the Ballymurphy massacre; since arriving from Belfast, they had already been condemned for excessive violence at another protest march a few days earlier. There commanding Officer Colonel Derek Wilford scorned the other regiments in Derry as “Aunt Sallies” and noted his men “weren’t going to hide behind barricades.” In later testimony, one of the paratroopers testified that in a briefing before the operation by an officer, “We want some kills.”

Fearing that the violence that would serve as a pretext for his mass arrest operation was dissipating, Ford pressured the command of the British Forces in Derry Brigadier Pat MacLellan to send in the Paras. MacLellan, as Derry commander, had previously implemented the official government policy of restraint that originated Wilford’s “Aunt Sallies” description and feared what the Para’s would do. Succumbing to pressure for Ford, he gave the Paras specific instructions for a limited operation to send one patrol on foot to make arrests in front of them, specifically that they were ordered: “not to conduct (a) running battle down Rossville Street.”

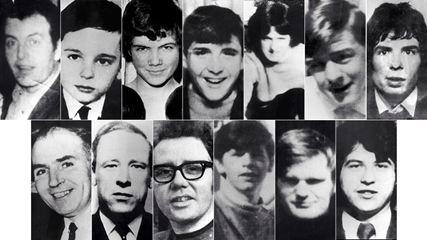

Col. Wilford was not going to obey MacLellan’s orders. Urged on by their sponsor General Ford yelling, “Go on Paras, go on and get them and good luck!” Wilford’s paratroopers charged into the Bogside on foot and in armored vehicles and commenced the “running battle down Rossville Street” MacLellan had explicitly ordered against. Discipline broke down immediately, with the Partropers opening fire on the crowd and engaging in indiscriminate beatings. Within 10 minutes, 13 people were dead; a 14th would die later from wounds he received.

Derry’s coroner, Hubert O’Neill, himself a retired British Army major, stated after his inquest into the killings:

“It strikes me that the Army ran amok that day and shot without thinking what they were doing. They were shooting innocent people. These people may have been taking part in a march that was banned, but that does not justify the troops coming in and firing live rounds indiscriminately. I would say without hesitation that it was sheer, unadulterated murder. It was murder.”

Yet, fifty years on, no one has been held accountable for those murders. Col. Wilford, who disobeyed orders, was a few months later awarded the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth. General Ford would later become commandant of Sandhurst, the U.K.’s West Point, served as ADC General to the Queen and was awarded the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. As they were getting these honors, their victims’ names were slandered for over 38 years, falsely accused of being armed, and terrorists. While the 2010 The Saville Report finally acknowledged the truth that the killings by the Parachute Regiment were unjustified, forcing British Prime Minister David Cameron ‘apologized’ on behalf of the British Government, the British government has yet to back that apology with deeds. Instead, it continues to thwart justice, going so far as to recently propose a statute of limitation for murders committed in Northern Ireland in defiance of all civilized norms of justice.

“The dead cannot cry out for justice. It is a duty of the living to do so for them.”

Lois McMaster Bujold

Neil F. Cosgrove, Historian