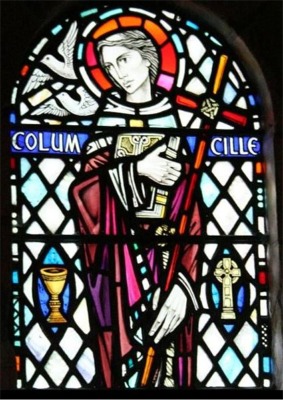

In the years following the missionary work of St.Patrick to Ireland, mainland Europe continued to slip further and further into the gloom of the Dark Ages. Only Ireland, which had transferred its ancient traditional love and appreciation of learning to the new faith and its classical traditions, was the flickering flame of civilization kept alive. Here it could have remained, at the edge of the known world, a fragile light that one strong wind could extinguish. Instead through the example of one man the light was returned to Europe where it would once again enlighten a continent. That man was St. Columcille, (Latinized to St. Columba).

In the years following the missionary work of St.Patrick to Ireland, mainland Europe continued to slip further and further into the gloom of the Dark Ages. Only Ireland, which had transferred its ancient traditional love and appreciation of learning to the new faith and its classical traditions, was the flickering flame of civilization kept alive. Here it could have remained, at the edge of the known world, a fragile light that one strong wind could extinguish. Instead through the example of one man the light was returned to Europe where it would once again enlighten a continent. That man was St. Columcille, (Latinized to St. Columba).

Columcille was born in Donegal in the year 597 A.D., some fifty years after the death of St. Patrick, in an Ireland that still had strong echoes of its Druid past as indicated by his birth name Crimethann (“the Fox”). He was of royal blood: a nephew of the current Ard Ri (High King of Ireland), his father a powerful Tyrconnell Chieftain, his mother the daughter of a Munster Chieftain. With such a pedigree and connections, young Crimethann could one day claim the high kingship for himself. He was schooled as a Bard and was considered one of the finest poets of his age. His love however was the Church, and it was from this love he was bestowed the name Columcille, translated “the dove of the Church.”

Columcille studied under St. Finian at Clonard until plague ravaged the area and forced the closing of the school. He returned home where his kinsman, the Prince of Tyrconnell, gave him land where he opened his famous monastery of Derry. Here Columcille showed both the unconventional oneness with nature that marked Irish Christianity, and perhaps evidence that there was still a bit of “the proud prince” in the young Abbott. Columcille built his church without the traditional alignment to face the rising sun so that he could preserve a stand of oak trees. By the time he was forty, Columcille had founded some forty churches.

Columcille had another passion: books. As the great libraries had vanished from Europe with many of their books burned, scholars from the classical world fled to Ireland bringing their books with them. The Irish Monks and Monasteries preserved books and copied them, even adding to them the first written copies of the early history of Ireland and its legends which had previously relied on oral tradition. Columcille’s love for books was such that it blinded his judgment: when visiting his teacher St. Finian, Columcille made a secret copy of one of his books, a rare copy of the Book of Psalms (called a Psalter) When St. Finian learned of the copy he demanded its return, Columcille refused. They agreed to have the dispute resolved by the High King Diarmuid. St. Finian argued that he should be able to decide when his book was copied and be allowed to ensure the copy was accurate (some copiers were not above adding their own embellishments); Columcille argued that books and their knowledge should be shared, and he did no harm to the value of the original book. Diarmuid reached a decision which still echoes today “To each cow its calf, to each book its copy.” It is the first recorded example of copyright law.

Though Columcille and St. Finian reconciled, some at the High King’s court appeared to have taken pleasure in seeing that the successful young monk was shown his place, and there was still enough of the noble in Columcille not to forget such a slight. When a short time later Diarmuid forcibly took into custody a young man who had been granted sanctuary in one of Columcille’s churches, it was the last straw. Columcille called upon his kinsmen and met Diarmuid and his followers in the battle of Cuildremne where Columcille was victorious but at a tremendous cost in lives.

Columcille realized the tremendous human cost of his pride and repented in a full confession. The penance he received carried a severity to match his sin: he was to leave the Ireland he loved and never see it again and he was to claim as many souls by conversion to the Church as he had caused to be lost in battle. Columcille and twelve companions boarded a coracle and sailed north till they found an island from which Ireland could no longer be seen: Iona off the coast of Scotland.

The humbled Columcille created a monastery and center of scholarship at Iona the likes of which had no parallel in Europe. Like Patrick had preached to the Irish, Columcille began to preach to the Picts and Scots. He was able to bring to bear his previous knowledge of royal politics, his bardic respect of their traditions and Christian compassion. His fame soon spread and he quickly claimed as many souls as had been lost at the battle of Cuildremne and many times more. So successful was his Monastery at Iona, Columcille had to limit the numbers of monks to 150. However, rather than simply turning applicants away, Columcille came up with a more generous solution: when the number of monks reached the limit, he made room by dispatching “twelve and one” monks with a mandate to found a new monastery. By the time of Columcille’sdeath over sixty monastic communities dotted the coast of Briton, each one carrying books and the flame of learning back to a darkened Europe, helping the Western World reclaim her lost past; an act for which all people, and not just the Irish, should remember him.