Ireland is often referred to as a land of myth and legend. The primary definition of both words describes a widely known story describing historical or natural events. Given that for centuries Irish history, like Irish music, was an aural tradition (and during much of English rule a necessity) passed down from one generation to the other the description is apt. However, in modern parlance “myth” and “legend” have become synonymous with sheer flights of imagination and untrue. Then again, what if they are instead echoes of history and those who lightly dismiss them are only showing a lack of imagination? For years scholars dismissed Homer’s accounts of the Trojan war as mere myths, until archeologist respecting the descriptions in Homer’s text found a very real Troy. What if someone was to treat Ireland’s alleged “myths” with the same open-minded scholarship? Case in point, the story of St. Brendan the Navigator.

The very real and historically undisputed St. Brendan was born near Tralee, County Kerry. Tradition holds that following Celtic custom at the age of one he was sent out to be fostered. His parents chose St. Ida who is usually regarded as second only to St. Brigid among Ireland’s Holy Women and is known as the “Foster Mother of Saints” as she would also foster the future St. Mochoemoc, St. Cumian and St. Fachanan. St. Ita and Brendan developed a strong bond which they maintained throughout their lives. When he was six he was sent to Saint Jarlath’s monastery school at Tuam to further his education. Brendan is one of the “Twelve Apostles of Ireland”, one of those said to have been tutored by the great teacher, Finnian of Clonard. At the age of twenty-six, Brendan was ordained a Catholic priest by Saint Erc

From the beginning the historical Brendan was an inveterate evangelist and voyager. Brendan’s first voyage was to the Aran Islands, where he founded a monastery. Between AD 512 and 530 Brendan founded monasteries in his native Kerry at Ardfert, and Shanakeel. He traveled several times to Scotland and the holy island of Iona where he met St. Columcille and to Wales to study under Saint Gildas. Returning to Ireland, he founded a monastery and convent in Annaghdown, where he spent his later years. He established churches in Galway and Inishglora and most notably at Clonfert, Galway where he was interred upon his death in 557 AD. This is the historically accepted Brendan.

However, what St. Brendan is most remembered for, and even at one time eclipsed St. Patrick in international recognition, is for a voyage that left no tangible evidence. It is described in the Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (The Voyage of Saint Brendan the Abbot), an account compiled by an Irish monk some two hundred years after St. Brendan’s death from various oral traditions. The Navigatio was a medieval bestseller. More than 100 Medieval Latin manuscripts of the Navigatio still exist, giving an indication of how many copies were originally made. In addition to versions in Middle English, French, German, Italian, Flemish and other languages.

The Navigatio describes a journey by St. Brendan and his fellows to a lush and green island paradise. Along the long journey they describe an island of sheep, another island of Birds (who apparently sang the Psalms!) and a hell like island and where the mountains belch rivers of flame and foul-smelling giants threw flaming rocks into the sea. The Navigatio describes St. Brendan coming upon gigantic towers of floating crystal in the ocean. The most famous incident of the story is when Brendan and his followers land on an island only to discover it was actually a giant whale. The Navigatio was given such credence in its time that medieval map makers showed “Brendan’s Island” on their charts up until the time of Columbus who is said to have studied material on Brendan’s voyage closely.

However, is it all myth or as some believe a religious allegory symbolizing the journey to salvation? If we take the known elements of Brendan’s life and the core elements of the Navigatio, looking at the world with medieval eyes and allowing for some poetic embellishment in two centuries of oral storytelling, what do we have? We know that the historical St. Brendan traveled to Iona, part of the collection of islands that make up the Hebrides. Beyond the Hebrides lies the Faroe Islands, Faroe being derived from an old Norse word for sheep (Brendan’s island of sheep). The islands of the Faroes chain have sheer coastal cliffs that harbor a wide variety of seabirds in the thousands that still today draw bird watchers from around the world (Brendan’s Island of Bird’s). Mountains billowing rivers of fire and flaming rocks being cast into the ocean sound like the volcanic activity that Iceland is famous for, activity which is accompanied by the foul smell of sulfur (Brendan’s island of giants). Would not “pillars of crystal floating in the sea” be an apt description someone may give on seeing an iceberg for the first time? Following this conjectural course, the Hebrides, Faroes, Iceland, could St. Brendan’s Island be North America, whom later documented explorers invariably described as a “lush, green paradise”? Adding more circumstantial evidence, the Norse sagas describe the land south of their settlements in Vineland (which itself was once considered “mythical”until recently confirmed by archeology) as “Irland it Mikla, it ” or “Greater Ireland.”

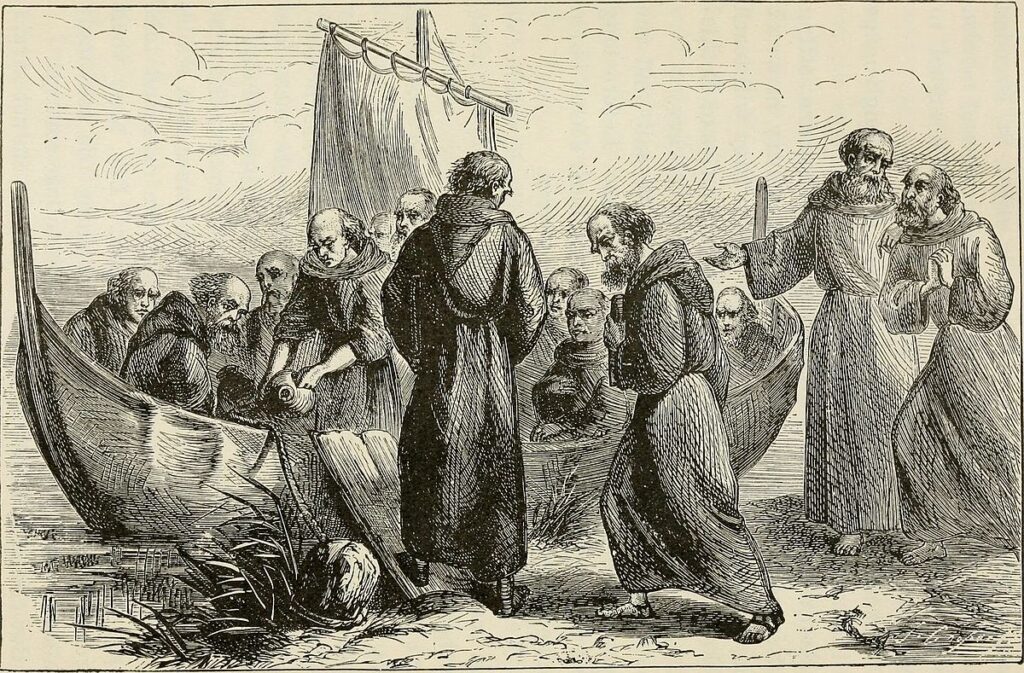

In 1976, explorer Tim Severin attempted to answer the question if a voyage to the new world by in the age of St. Brendan was feasible. He built a traditional Irish boat, a currach, using the description in the Navigatio and traditional materials of the time. Casting off from the Dingle Peninsula and following the prevailing winds across the northernmost part of the Atlantic Ocean, Severin and his crew were able to island-hop their way to Newfoundland. Severin noted that during the voyage he encountered pods of whales who seemed fascinated with their leather hide covered currach, reminiscent of the Brendan and the whale story.

Does this prove that Irish Monks or specifically St. Brendan traveled to America centuries before Columbus and the Vikings? No, but it should open our minds to the possibilities; it should cause us to give greater respect to Ireland’s legends and challenge any attempts to easily dismiss them as mere “blarney”.