There was a time when mouse clicks and tweets did not drive reporters; they actually went out, sometimes at great personal peril, to find the news. One such reporter and a pioneer of investigative journalism was Irish American Nellie Bly.

Nellie Bly was born Elizabeth Cochrane on May 5, 1864 in Cochran’s Mills, now part of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her father, Michael Cochran (Elizabeth would add the ‘e’ to the last name later), was the son of an immigrant from Derry who had started as a laborer and had prospered to the point of buying the local mill after which the town was named. Elizabeth was one of five children Michael had with his second wife, Mary Jane Kennedy. Michael Cochran had ten children by his first wife.

The young Elizabeth’s world suddenly collapsed when her father died when she was six years old without leaving a will. The Court directed that his assets be sold and divided amongst the children of both marriages, putting her mother in precarious financial circumstances. Her mother remarried, but the second husband was abusive, resulting in a divorce that further strained the family’s finances, forcing Elizabeth to drop out of school where she had been studying to be a teacher.

Given the experiences she had so far endured in her young life, it was little wonder that a condescending article entitled “What Girls are Good For” in the Pittsburgh Dispatch provoked a fiery response from young Elizabeth, who penned a letter to the editor dramatically signed “Lonely Orphan Girl.” The editor was so impressed with the rebuttal that he ran an ad asking whoever wrote it to come forward and identify herself. Meeting Elizabeth Cochrane and impressed with her spirit, he offered her a job. It was customary for women reporters to write under a pseudonym; the editor suggested “Nelly Bly,” the subject of a popular Stephen Foster song. When it went to print, “Nelly” was accidentally changed to “Nellie” and stuck; Nellie Bly was born.

Showing her spirit for adventure, Bly traveled to Mexico despite knowing no Spanish lived and lived among the Mexican people, sending back reports on their daily lives and customs. However, her streak as a crusader also manifested itself, and she soon had to flee the country before being arrested for criticizing the government of dictator Porfirio Díaz. Her dispatches were later compiled into a book entitled “Six Months in Mexico.”

Despite proving herself as an investigative reporter, Bly soon found herself given nothing more than “domestic topics” to write on despite her protests. One day her editor came into the newsroom to find a note from Bly stating, “I am off for New York. Look out for me.”

Despite being an experienced reporter, Bly found it nearly impossible to break into New York journalism. Bly eventually talked her way into Joseph Pulitzer’s The World newspaper offices with a proposal to do an investigative piece on New York City’s notorious Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) by having herself committed as a patient. As events would later prove, this was a hazardous undertaking; it was later admitted that they were not clear on how they would get her out of the asylum at the time.

Bly got into her character with a vengeance. She practiced a “faraway expression in a mirror” and stopped practicing personal hygiene. She then dressed in tattered second-hand clothes and checked herself into a boarding house for women, where she began looking for a non-existent trunk and ranting. Within 24 hours, her outbursts had the residents calling the police in fear of their lives. A judge remanded Bly to Bellevue Hospital’s psychiatric ward, where the chief doctor diagnosed her as “delusional and undoubtedly insane.” She was committed to Blackwood Island.

Bly would spend ten days in the hell of Blackwood’s asylum. She would later write of spoiled food, lack of warm clothing and a treatment of ice-cold baths that simulated drowning. The matrons were abusive; some were actually inmates from a penitentiary that shared the island, who regularly beat and choked the patients. Even worse were prolonged periods of social isolation. Bly wrote:

“Take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her no reading and let her know nothing of the world or its doings, give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck.“

More concerningly, Bly found that many of the women confined at the asylum were sane. One patient was a German woman whose only malady was that she had such a thick accent that she had been diagnosed as speaking gibberish. Some were inconvenient wives whom their husbands had put away. Ominously, Bly dropped her insane act once she had achieved her goal, yet found “the more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier I was thought to be.” It was clear that once a woman was committed, it was virtually impossible to be released.

After ten days, the lawyers for “The World” appeared with a court order for her release. Bly’s expose “Behind Asylum Bars,” which would later form the basis of a book, “Ten Days in a Madhouse,” became a nationwide sensation and Bly a national celebrity. The attention she raised resulted in the appropriation of an additional one million dollars (a tremendous sum in the late 19th century) to the annual budget for the mentally ill-treatment in New York City.

Bly would not be out of the public consciousness for long. She proposed to Joseph Pulitzer recreating the fictional journey of Phineas Fogg in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days and to complete the trip in even less time. Pulitzer resisted sending her. He told her that her gender would make the trip impossible. “Very well,” Bly replied, “Start the man, and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.” By this time, Pulitzer knew it was no idle threat and conceded.

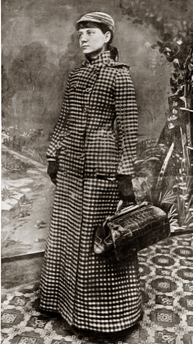

Bly began her trip with but a single carry-on bag. When she reached Paris, she had lunch with Jules Verne, who offered her his encouragement. The public followed her daily reports with fascination as she traveled lands they had never heard of. When she New York, Bly was unaware that a competing paper had dispatched their own woman reporter in an attempt to beat her; their reporter turned out to be no competition as while she wrote flowery prose about scenery and sunsets, Bly reported on people and their customs. When Bly arrived in California, she was behind schedule by two days due to storms in the Pacific but found that Pulitzer had chartered train waiting to bring her home. She arrived back in New Jersey on January 25, 1890 completing the trip in just over seventy-two days. Nellie Bly was a national sensation.

Bly continued to be a crusading reporter for several more years, but never equaled the fame of her earlier exploits. She married millionaire manufacturer Robert Seaman, a man forty-two years her senior, and left Journalism. Upon her husband’s death, she took over his Iron Clad Manufacturing Co., which made steel containers. As with all her endeavors, Bly threw all her energies behind it. She obtained several patents in her own name for designing new containers. However, as if coming full circle to her earlier life, finances proved her bane. As biographer Brooke Kroeger noted, “She ran her company as a model of social welfare, replete with health benefits and recreational facilities. But Bly was hopeless at understanding the financial aspects of her business and ultimately lost everything.”

Bly briefly returned to journalism, even covering WW I from the eastern front, before succumbing to pneumonia at the age of 57; a representative of a type of journalism which we should seek to recapture and an Irish American we should always remember.