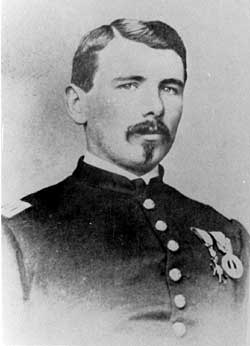

Few moments in American history are more mythologized or more debated than those of the Seventh Cavalry at the Little Big Horn. Myth has the power to preserve the names of people who would otherwise be forgotten, but often at the price of losing the true person. One example of this is Irish American Captain Myles Keogh.

Keogh was born on March 25,1840 in Leighlinbridge, County Carlow at Orchard House, a building that still stands today. His family appeared to have lived in secure circumstances, his father John was a comfortable gentleman farmer and his mother was from a prosperous and distinguished family from Rathgarvan, County Kilkenny. One of the persistent myths associated with Myles Keogh is that his father was an officer in the 5th Royal Irish Lancers, this to explain Myles’ familiarity with the tune “Garryowen” which in another myth he is said to have introduced to the 7th cavalry. In fact, Keogh’s family was staunchly Catholic and one of Keogh’s uncles was hung for his participation in the 1798 rebellion. Such pedigrees did not receive officer’s commissions in the English cavalry of the 19th Century.

Keogh was born on March 25,1840 in Leighlinbridge, County Carlow at Orchard House, a building that still stands today. His family appeared to have lived in secure circumstances, his father John was a comfortable gentleman farmer and his mother was from a prosperous and distinguished family from Rathgarvan, County Kilkenny. One of the persistent myths associated with Myles Keogh is that his father was an officer in the 5th Royal Irish Lancers, this to explain Myles’ familiarity with the tune “Garryowen” which in another myth he is said to have introduced to the 7th cavalry. In fact, Keogh’s family was staunchly Catholic and one of Keogh’s uncles was hung for his participation in the 1798 rebellion. Such pedigrees did not receive officer’s commissions in the English cavalry of the 19th Century.

The staid life of a farmer was not for young Myles and from an early age he demonstrated a romantic and adventurous spirit. In 1860, the Papal States were being threatened by the revolutionary forces of Garibaldi. Pope Pius IX put out a call for young Catholic men to help preserve the independence of the Papacy from attack. The young men of Ireland were quick to answer the Pontiff’s call with over 1,400 Irish traveling to Italy to serve, among them a 20-year-old Myles Keogh who was commissioned as a lieutenant. Keogh and his Irish Battalion distinguished themselves by their gallant defense of the port city of Ancona. In recognition of his valor, Keogh was awarded the Pro Petri Sede and Ordine di San Gregorio medals for valor in addition to being appointed a lieutenant in the “Company St. Patrick” of the Papal Guards.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, the Union Army was desperate for experienced officers, most of the officers of the old army being southerners who went with the Confederacy. Irish American Archbishop John Hughes was sent by the Lincoln administration to recruit experienced officers from the veterans of the Papal wars. Myles Keogh and two of his comrades Daniel J. Keily of Waterford and Joseph O’Keeffe, nephew of the Bishop of Cork, volunteered. The three traveled to the United States and were commissioned as Captains. All three would distinguish themselves.

Keogh would participate in over eighty engagements and distinguish himself in most of the major battles of the Civil War. In his first battle at Port Republic, a patrol he was leading nearly captured Stonewall Jackson. As a member of General John Buford’s cavalry, Keogh earned a brevet promotion to Major for bravery at Gettysburg as part of the cavalry’s heroic delaying action during the first day of the battle that proved key to the eventual Union victory Keogh later transferred to the Western Theater of the War where he served as chief of staff to General Stoneman. Keogh would be active until the end of the war, leading raids in Georgia, North Carolina and Virginia. Before the Civil War ended, Keogh would once again be promoted for bravery, attaining the rank of Lt. Colonel. Union General Schofield called Keogh “one of the most gallant and efficient young cavalry officers I have ever known.”

Unfortunately, the success Keogh had enjoyed in the Civil War was followed by sadness and disappointment in the post war years. Keogh’s fellow Irishmen and Papal War comrades Keily and O’Keeffe had not survived the war. A woman that Keogh had hopes of marrying had died suddenly, a sadness Keogh never fully recovered from. With the shrinking of the peacetime army, Keogh’s rank was reduced from Lt. Colonel to Captain and he was assigned to the seventh cavalry under Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer.

Despite popular myth, the relationship between Keogh and Custer was not a close one, and in fact may have been contentious. The legend that Keogh introduced Custer to the tune “Garryowen” which resulted in it becoming the regimental march of the 7th is unlikely. “Garryowen “had been a popular tune for many years and Custer had heard it many times as a cadet at West Point.

When in June 1876 Keogh rode out with Custer as the Captain of Company I of the seventh cavalry, it appears that Keogh had a premonition of his death. Keogh had inherited his Mother’s family estate in Ireland, but had signed it over to his sister. He had taken out a life insurance policy and had requested that the wife of one of his officers burn his personal papers in the event of his death. Finally, Keogh left instructions that in the event of his death, he wished to be buried near friends in Auburn, New York.

The full details of the battle of the Little Big Horn may never be known; even eyewitness testimony of Native Americans at the battle was taken years after the events of June 25, 1876 and is often contradictory. However, there is evidence that Myles Keogh died as he had lived, with honor and courage. When a burial party arrived three days after the battle, Keogh’s body was found at the center of a group of troopers that included his two sergeants, the company trumpeter and guidon bearer, indicating that Keogh and his men had died as part of their own “Last Stand”. Also noted was that Keoghs body alone had not been mutilated, perhaps because the Native Americans were intimidated by the “medicine” they saw in the Agnus Dei he wore on a chain about his neck, or because of his bravery in his final moments, most likely a combination of both. The only survivor of the 7th Cavalry found at the Little Big Horn was Keogh’s badly wounded horse, Comanche, wounds that indicated that he and his rider had been in the thick of the action. Comanche would be nursed back to health and adopted as a revered regimental mascot. The animal’s fame as “the sole survivor of the 7th” quickly spread and ensured that the name of his rider, Myles Keogh, would be remembered.

There is something tragically Irish in that gallant Myles Keogh is not remembered for his proven bravery and deeds in the Civil War and at the Little Big Horn, but is instead remembered in a 19th Century version of an “Urban Legend” for introducing the “Garryowen” as a regimental march and for being the owner of a horse that by chance survived a battle. While not accepting these myths at face value, we should be grateful that they have at least preserved the memory of a gallant Irish American who typifies many, many more whose deeds go unsung.

Historian – Neil F. Cosgrove

[ratings]

Did You Know That

- Though not having the benefit of myth and legend to preserve their names, Keogh’s comrades from the Papal Army both distinguished themselves in the service of their adopted county:

- In his first battle at Port Republic Daniel J. Keily would distinguish himself. Seeing an abandoned artillery piece that was about to be captured by the enemy, Keily rallied some men and continued to fire the gun under a hail of enemy bullets till it could be removed. A Colonel Carroll witnessing Keily stated, “I do not think I ever saw a more perfect piece of coolness & heroism”. He would later in the battle receive a serious wound while leading a counterattack. He would finish the war as a brevet Brigadier General, but would die of fever soon after the war concluded.

- Joseph O’Keeffe would serve on the staff of fellow Irish American General Phillip Sheridan, an ancestor of Division III’s own Phil Sheridan. He would accompany Sheridan on his famous ride across his lines at the battle of Cedar Creek in 1864. O’Keefe would attain the rank of brevet Lt. Colonel before being killed in one of the last battles of the Civil War at Five Forks

- Keogh’s first commanding officer was County Tyrone native General James Shields. An active politician both before and after the war, Shields is the only man to represent three different states (Illinois, Minnesota and Missouri) in the U.S. Senate.

- At one point in his career Shields took exception to remarks published about him by a lawyer named Abraham Lincoln and challenged him to a duel. Lincoln had the choice of weapons and irreverently chose ‘broadswords.” Literally disarmed by Lincoln’s humor, the quarrel was ended and the two men became friends.

- Another Irish American hero of the Battle of Gettysburg was Irish American Colonel Patrick Henry O’Rorke. O’Rorke was killed while successfully leading his men in defense of the key position of Little Round Top. He was first in his 1861 class at West Point, fellow classmate George Armstrong Custer was last.

- Besides the 7th Cavalry, the tune Garryowen is the regimental march of the NY Fighting 69th. Garryowen is located in County Limerick and was popular destination in the 18th Century for young merrymakers whose exploits the song recounts