In the early days of Baseball, Irish Americans dominated the sport and helped transform it into America’s national pastime. Young men made strong through the strenuous physical labor in what were often the only jobs available to them took what little relaxation they had in the new sport and soon came to dominate it and were innovators who transformed it into the game we know today. Perhaps no one impacted Baseball more in its formative days than Michael “King” Kelly.

Michael Joseph Kelly was born in Troy, New York, on New Year’s Eve, 1857, the son of Irish immigrants. At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Kelly’s father enlisted in the Union Army. The family followed him to Washington, where the young Kelly may have first been exposed to the new game of Baseball.

After the Civil War, the Kelly’s moved to Paterson, New Jersey. Kelly’s father passed away in 1871, ending the thirteen-year-old boy’s formal education as he left school to work hauling coal and as a ‘bobbin boy’ in a textile mill. However, his love was still Baseball, and it was not long before he gained the notice of the newly formed professional teams.

In 1878, Kelly made what would now be termed his Major League debut (the term ‘Major League’ not having been coined yet) for the Cincinnati Red Stockings (now the Cincinnati Reds), for whom he played for two years before the team fell on hard times and released its players. Kelly was acquired by the Chicago White Stockings (the forerunners of today’s Cubs). He would become the preeminent star of the game, earning two league batting championships, leading the league for three seasons in scoring, and playing on four of his career six championship teams. Kelly was primarily a catcher and outfielder but would play all positions throughout his career. Standing nearly six feet tall, talented, and with distinctive good looks, Kelly was soon a fan favorite in what was one of the Nation’s media capitals and was soon a household name.

After the 1886 season, Kelly was sold to the Boston Beaneaters (the forerunners of today’s Atlanta Braves) for a record $10,000, earning Kelly the nickname “10,000 Beauty“. However, in heavily Irish Boston, he was more commonly known as “King Kelly” or “The Only.”

Kelly was both one of the game’s great innovators and characters. It is believed he was the first catcher to use a chest protector, wear gloves, and use signs to communicate with the pitcher. The Baseball Hall of Fame cites him as originating the ‘hit and run’ play, the ‘double steal’ and an early form of the infield shift. Kelly was also not above a little ‘gamesmanship.’ It was noted that he frequently would cut corners (sometimes by 20 feet) in rounding the bases when he knew that the games then only one umpire was distracted by play elsewhere on the field. In playing the outfield, Kelly often had a spare baseball hidden in his jersey; late in one game, as the light was failing, Kelly made a spectacular dive for a ball lined to the outfield. Kelly popped up proudly, displaying the ball in his hand. When his teammates complimented him on his catch, Kelly laughed, ‘Not at all; it twent a mile above my head.’ Some claim Kelly’s popularity in Boston also led to another innovation; young boys in Boston would ask him for his signature to prove they met him, giving rise to the autograph.

However, Kelly’s most significant notoriety came from another of his innovations, ‘the hook slide.’ Before Kelly, ballplayers would attempt to steal a base by running at it directly; Kelly developed the technique of running to the opposite side of the bag, sliding past it, and making contact with his hand. Kelly stole 50 bases or more bases a season for five consecutive years (1886-90) and stole a career-high 84 bases for Boston in 1887. He stole six bases in one game and five in a game multiple times. Kelly was one of the first players to regularly steal third base and home, often in succession.

A print of Kelly sliding soon became a required fixture in all Boston bars. The chant of the Boston crowd ‘Slide Kelly, Slide!” became the basis of a song that, when recorded by the Edison company, became America’s first ‘pop hit,’ the previous recordings having been either Opera or Religious songs.

Sadly, Kelly was also a pioneer in a problem that has been too frequently repeated among professional athletes thrust from poverty into the spotlight of fame and prosperity. Kelly had a reputation for both generosity and being a hard partier. While making unbelievable money for his time, he spent it as fast as it came in. A teammate observed that “[Kelly] was a whole-souled, genial fellow, with a host of friends and but one enemy, that one being himself.”

A testament to Kelly’s character comes in a story from 1890 when labor unrest between team owners and players resulted in many ballplayers, including Kelly, breaking away to form their own Players League. Kelly became a player-manager for the Boston Reds. With more noble sentiment than money, the league was soon in trouble. During a series of games in Chicago, Kelly met with Albert Spalding, representing the owners of the National League. Spalding put a $10,000 check in front of Kelly, telling him he could have that and a three-year contract as a figure he could name if he left the Player League and rejoined the Beaneaters. According to Spalding, Kelly asked to think about it as he went to take a walk outside. Returning, Kelly said, “I’ve decided not to accept’. A shocked Spalding said, “What? You don’t want $10,000?” Kelly replied, “I want the $10,000 bad enough, but I’ve thought the matter all over, and I can’t go back on the boys. And, neither would you.”

Spalding shook Kelly’s hand and, knowing he was hard up, lent him $500. Kelly and his team would win the only Championship of the Players League before its demise after one season.

Hard playing on the field and hard living off it had caught up with Kelly, and his skills began to decline. Kelly retired in 1894 after sixteen seasons with little of the money he had earned. In another first for a ballplayer, Kelly wrote his autobiography. Kelly attempted to capitalize on his notoriety, good looks, and good humor on the vaudeville stage. While sailing from New York to Boston for a theatrical performance, Kelly contracted pneumonia dying three days later, on 8 November 1894, at the age of 36.

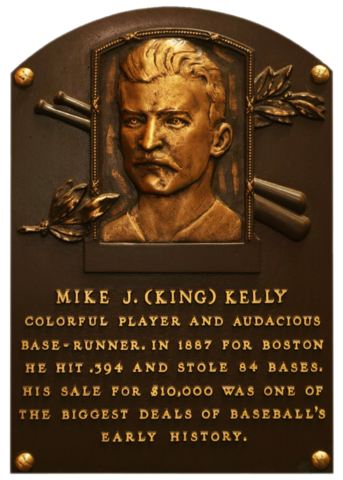

Michael “King” Kelly was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945 by the old-timers’ committee. It says something of the Irish influence in Baseball that the NY Times reported that inducted with him were “Bresnahan, Brouthers, Clarke, Jim Collins, Delehanty, Duffy, Jennings, James O’Rourke and Robinson.” Sadly, there were no immediate family members at the ceremony, his one child having died shortly after his death and his wife dying several years before he was inducted.

Lee Allen, a historian with the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, “Kelly, in his day, was as popular a figure as Babe Ruth would later be, and there was hardly a boy in the land who did not follow the daily doings of The King.“

Certainly, ‘King’ Kelly deserves to be better remembered by the game he helped shape.

Neil F. Cosgrove, Historian

© Neil F. Cosgrove