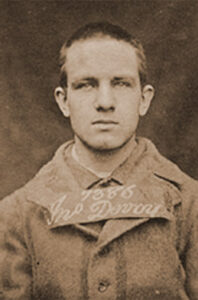

In a mid-19th century classroom in one of Ireland’s new “National Schools”, pointed to as an example of a more “progressive” British policy in Ireland as they provided non-denominational education, a teacher faced a rebellion. One of his young students, a short, dark-haired son of a brewery clerk, refused to sing “God Save the Queen” as required at the start of the school day. The teacher summoned the superintendent, whose mood was not improved when confronted by the young rebel. Though seated in the front row of the class because he already suffered from extreme nearsightedness, there was no mistaking the look of defiance in those blue eyes. The superintendent bellowed to his defiant charge ‘Sing Sir!” only for the boy to refuse. The superintendent then applied the standard Victorian educational method to address diversity; he smashed a chalkboard slate over the young nonconformist’s head. The boy missed several days of school due to “lightheadedness” (likely a concussion). When the sadistic superintendent attempted to further chastise the boy (this time with a cane) for his absence, the young dissident charged him pushing him back and delivered a swift kick to his knees. The boy, John Devoy, was expelled for his first fight for Independence.

John Devoy was born 1 September 1842 near the village of Kill in County Kildare. Nationalism was a family legacy. While Devoy’s father’s nationalism took a constitutional approach as a supporter of O’Connell and the Repeal Movement, John’s patriotism would favor his namesake; a maternal great-uncle who fought in the Rising of ’98. Though born on the eve of the “Great Hunger”, John Devoy would be spared the worst of that tragedy of suffering by the family relocating to Dublin. There his industrious and literate father secured employment at Watkins Brewery, providing a secure childhood at a time when the Great Hunger was sending across the Atlantic the millions of Irish emigrants who would define John’s later life.

In early 1861, at the age of eighteen years, John Devoy took the Fenian oath. The oath bound the young Devoy to work for the establishment of an Irish Republic. Devoy would dedicate himself to the Fenian cause with the same resolute determination he showed as a schoolboy while similarly bearing innumerable hardships with the same fortitude. Devoy’s father became aware of his son’s political activity and the family argument that ensued only made the rebellious teenager more determined. He ran away and joined the French Foreign Legion to gain military experience he could later use in the fight for Ireland’s freedom. Unfortunately, the youthful dream of adventure met the hard reality of being assigned to an engineering company (likely due to his eyesight) in Algeria. He was released under his commanders signature a year later (though some sources incorrectly say he deserted) and returned to Ireland.

Devoy reported back to the Fenian executive led by James Stephens. The Fenians were in the midst of planning a new rebellion with a bold new strategy composed of three parts. First was the traditional recruitment of the young men of Ireland such as Devoy to the cause. However, past rebellions had always suffered from the lack of trained men and arms no matter how enthusiastic the support of this traditional recruiting source. This was to be radically solved by the other two legs of the strategy. The second part would be the active recruitment of Fenians from within the ranks of the British army. Fully sixty percent of the 26,000-strong British garrison in Ireland were Irishmen who served not out of loyalty to the crown, but as a desperate last resort to escape hunger and poverty. Every soldier who took the Fenian oath would achieve the dual purpose of undermining Britain’s ability to respond to a rebellion and providing another trained man and his weapon to the cause. The third part was the realization that there was now a third force in Ireland’s struggle: Irish America. Those starving emigrants that had been driven into exile in America had prospered in their adopted land. They and their descendants were now a source of funding and battle-hardened men forged in America’s Civil War.

To young Devoy fell the responsibility to recruit Fenians from the British Army. As with everything he attempted, Devoy rose to the task with total commitment and tireless zeal. He recruited soldiers who in turn recruited their messmates. Devoy even clandestinely administered the Fenian oath to soldiers as they stood guard in their sentry boxes. At one time, falling back on his Foreign Legion training, Devoy donned a British Army uniform to enter a barracks to gather intelligence on the Army’s strength and morale. At its height, it is estimated that the Fenians had over 80,000 men pledged to a coming rebellion, of which over 20,000 were Devoy’s converted British soldiers.

However, it was soon apparent that Stephens, while a great visionary, was not a man to lead a rebellion. While promising that with the end of the American Civil war 1865 would be “a year of action”, Stephenson continually dithered. The success of the Fenians was also its vulnerability; a force of nearly one hundred thousand men could not be kept secret forever. British intelligence was soon reporting an alarming number of men in “felt hats and square-toed boots”; American fashions indicating that Irish Civil War veterans were returning to Ireland with vengeance in their hearts. Suspicions were confirmed when documents inadvertently left at a train station detailed a planned Irish uprising. The British lion had finally awoken to what was happening in its oldest colony. In September 1865, the offices of Stephens’ paper The Irish People was raided and everyone on the premises arrested. Stephens was later apprehended and confined in an isolated wing of Richmond prison to await trial. Devoy immediately turned his energies to a rescue plan. With the help of the prison hospital superintendent who was a sworn Fenian with access to the prison’s keys Stephens escaped and was spirited to France.

The Stephens escape was a propaganda coup for the Fenians. Ireland was seized with sudden enthusiasm for Fenianism and the prospects of independence. However, Stephens continued to lack the nerve to instigate the rising and the British were now fully aroused. Suspect Army regiments were transferred from Ireland to the remotest parts of the empire. Suspending Habeas Corpus, British authorities made mass arrests including John Devoy and some of the soldiers he recruited. Devoy was sentenced to 15 years penal servitude, but it would be half a century before he would walk Ireland a free man again. Sadly, Devoy would also be separated from the only other passion he allowed himself, a young girl named Eliza Kenny to whom he was engaged.

For the next five years Devoy would be an unwilling guest at some of Britain’s most notorious prisons: Mountjoy, Millbank, Portland and

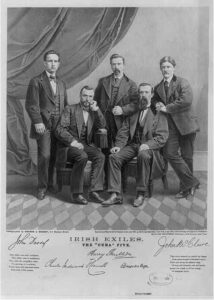

Chatham. Fenian prisoners were selected for “special attention” by sadistic guards. As might be expected, the former defiant schoolboy was hardly a model prisoner and orchestrated several prison strikes and other acts of disobedience which were harshly punished. Finally, in January 1871 in response to public outcry concerning reports on how the Fenian prisoners were being mistreated, Devoy, along with four other Fenians including O’Donovan Rossa, was released on condition of accepting exile to the United States. Known as the “Cuba Five” for the name of the steamship that brought them to America, they were given a hero’s welcomed by Ireland’s exiled children in America. However, Devoy was appalled at what can only be described as the slapstick jockeying of various Irish American Groups and politicians as they pushed and shouted at one another to claim pride of place in welcoming the exiled Fenians and leverage their notoriety for their own purposes. Devoy saw the vast potential of Irish America, but it had to be unified to be an effective force in Ireland’s fight for freedom. It would be to this cause which John Devoy would devote the rest of his life and will be continued in next month’s history.