The commentator Walter Winchell paid tribute to the patriotism and courage of Irish Americans during his St. Patrick’s Day broadcast of 1945 observing: “You can’t strike the American Flag without expecting to get hit back by some Irishman.” Perhaps Winchell was thinking of the uncertain days when an ill prepared America was thrust into a World War by the sneak attack by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. In those dark days it appeared that the forces of freedom were everywhere in retreat against what seemed the unstoppable advance of Hitler’s Germany in Europe and Imperial Japan in the Pacific. The American flag had been struck, and a fearful nation needed someone to strike a blow back to show that the forces of the enemy were not invincible. As Walter Winchell had observed, they found that person in an Irish American Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare.

The commentator Walter Winchell paid tribute to the patriotism and courage of Irish Americans during his St. Patrick’s Day broadcast of 1945 observing: “You can’t strike the American Flag without expecting to get hit back by some Irishman.” Perhaps Winchell was thinking of the uncertain days when an ill prepared America was thrust into a World War by the sneak attack by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. In those dark days it appeared that the forces of freedom were everywhere in retreat against what seemed the unstoppable advance of Hitler’s Germany in Europe and Imperial Japan in the Pacific. The American flag had been struck, and a fearful nation needed someone to strike a blow back to show that the forces of the enemy were not invincible. As Walter Winchell had observed, they found that person in an Irish American Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare.

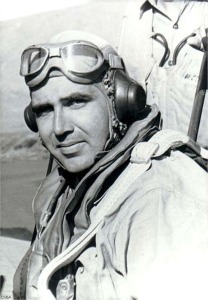

O’Hare was born in St. Louis on March 13, 1914. His father Edgar (though he preferred Edward and was known as ‘E.J.”) was a first generation Irish American while his mother was of German descent. O’Hare developed a close relationship with his father who had a profound influence on his life. The elder O’Hare appeared to have been the ideal American success story: he worked in a produce market and later his father’s restaurant to support his family while studying law at night. He had the good fortune to represent the inventor of the “mechanical rabbit” used in dog racing and soon made a fortune with an interest in several dog and horse racing tracks. This provided an idyllic lifestyle for the young Edward O’Hare with summer country vacations, where in addition to sailing and fishing, he learned to shoot and become a proficient marksman. The elder O’Hare was fascinated with aviation, and flew whenever possible, often taking young Edward with him and persuading the pilot to let his son take the controls for a few minutes, inspiring a lifetime love offlying in the boy. There was, however, one thing the ambitious and driven E.J. O’Hare could not abide, not even in his son: laziness. When young Edward approached his father one day for the keys to the car to drive next door to a bakery so he could buy pastries for himself, E.J. had had enough and sent his son to a military academy thus setting Edward on the path to a military career. Edward would eventually be appointed to and graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy. After an obligatory tour as a ships officer, O’Hare transferred for training as an aviator.

Upon completion of training he was assigned to VF-3 flying the F4F-3 Wildcat fighter. On February 20, 1942, VF-3 was assigned to the carrier USS Lexington which was part of a task force attempting to raid the strongly held Japanese base at Rabul. While off the coast of New Ireland, the task force was spotted by the enemy. The Japanese sent multiple waves of bombers against the task force with the main objective of sinking the Lexington. O’Hare was part of a flight that had scrambled to go after one wave of Japanese Bombers, when in flight a second wave was detected only 12 miles away from the carrier. O’Hare and his wingman were the only ones close enough to engage the fast approaching enemy. Turning to engage, O’Hare’s wingman reported that his guns were jammed, all that stood between the Lexington and 8 Japanese medium bombers was O’Hare and his lone Wildcat which had only enough ammunition for 34 seconds of firing.

Without hesitation, O’Hare pushed the throttle to full and engaged the first Bomber. Firing a burst, his aim was so accurate one of the engines was shot from its housing. One by one, O’Hare maneuvered and attacked the wave of bombers until he had shot down five in less than as many minutes. So devastating was O’Hare’s attack that when additional fighters from the Lexington arrived, the flight commander reported that he saw three enemy bombers falling in flames simultaneously. The reinforcements were timely for O’Hare was out of ammunition. It was later calculated that O’Hare’s gunnery was so accurate that he had used only 60 rounds of ammunition per bomber shot down.

“Butch” O’Hare was the first Naval Ace of WW II. In the opinion of the commanding officer of the Lexington, O’Hare single handedly saved the Lexington from serious damage or even loss at a time when a Pearl Harbor depleted U.S. Navy could ill afford to lose a carrier. O’Hare would be awarded the Medal of Honor, the first Naval Aviator to receive the nation’s highest honor. Tragically, O’Hare would lose his life as part of the first night fighter operations launched from a U.S. carrier on November 26, 1943.

Today if you go to Terminal 2 in Chicago’s O’Hare Airport you will see a restored F4F-3 Wildcat painted in the markings of O’Hare’s plane on the day he saved the Lexington and earned the Medal of Honor. Sadly, most people hurriedly pass the plane, never stopping to consider the brave man it pays tribute to, or the hope he gave a nation when hope was most needed. While others may forget “Butch” O’Hare, we as Irish Americans never should.

Historian Neil F. Cosgrove

Did You Know That?

• The second highest scoring ace in World War II was Major Thomas McGuire with 38 confirmed kills. McGuire was also awarded the Medal of Honor. Born in Ridgewood NJ, McGuire Air Force base is named for him.

• The U.S. Navy had only two aces in Vietnam: Naval Aviator Randy “Duke” Cunningham and his Radar Intercept Officer William “Willy Irish” Driscoll.

• Before the famous “Doolittle Raid”, the feasibility of launching the B-25 Bomber from the flight deck of a carrier had to be tested. The successful test flights were carried out by Lieutenants John Fitzgerald, and James McCarthy

• One of the RAF’s greatest aces during the ‘Battle of Britain’ was Brendan Eamon Fergus Finucane, nicknamed ‘Paddy’. Finucane’s father had been a member the Irish Volunteers and served under Éamon de Valera’s command in the 1916 Rising. His family emigrated to England and when Britain declare war young Paddy joined the RAF, but made it clear whom he was fighting for with a vibrant green shamrock on his plane. He would be credited with 26 confirmed kills (plus an additional 6 shared) and become the youngest wing commander in the history of the RAF before his death at age 21.