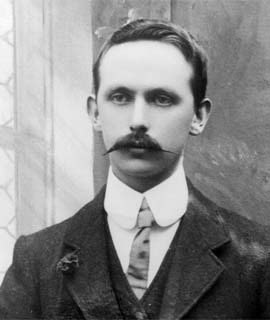

Of the seven signers of the 1916 Proclamation Eammon Ceannt is likely, and unjustly, the least known. He did not possess the eloquence of Padraig Pearse nor the charisma of a James Connolly, but what he did possess a single-hearted devotion to Ireland and her people’s freedom and a willingness to sacrifice all in their cause. He deserves to be far better recognized as one of Ireland’s great patriots

Of the seven signers of the 1916 Proclamation Eammon Ceannt is likely, and unjustly, the least known. He did not possess the eloquence of Padraig Pearse nor the charisma of a James Connolly, but what he did possess a single-hearted devotion to Ireland and her people’s freedom and a willingness to sacrifice all in their cause. He deserves to be far better recognized as one of Ireland’s great patriots

As with so many of the leaders of 1916, there was little in Ceannt’s early life that would foreshadow him as a Rebel, He was born Edward Kent in 1881 Ballymoe, County Galway in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Barracks where his father James was a constable. Accounts of his childhood showed a shy boy who would give his pocket money to friends to buy his candy as he was too bashful to ask himself. Yet burning in young Eamonn was a deep quiet intensity that would be the hallmark of his life; he would never undertake anything without giving 100% of himself. Like so many other of the leaders of 1916 he was a product of Christian Brothers education and would be awarded honors in Latin, English, French, German, Arithmetic, Algebra and Drawing.

Ceannt, like many others in his generation, felt the spark of Irish nationalism during the centenary celebrations marking the 1798 rebellion. As with everything in his life that small spark soon developed into an impassioned blaze. In 1899 he joined the central branch of the Gaelic League, where he met Padraig Pearse. He became a fluent Irish speaker and soon adopted the Irish form of his name Eammon Ceannt. He taught Irish and developed a reputation as an inspiring teacher. Always having a talent for music, Ceannt soon mastered the Irish war and uileann pipes, mastering them to such an extent that in 1908 he lead in a group of Irish Athletes competing in Rome and was subsequently invited to do a special performance for Pope Pius X. He formed the Dublin Piper’s Club and was soon publishing a journal on an old printing press he had acquired. He took it upon himself to scour the Irish countryside looking for old pipers whom he then invited with expenses paid to the club in Dublin to share their tunes. If it had not been for Ceannt ‘s efforts, a considerable part of Ireland’s musical legacy may have died with these men and for this work of preserving our Irish heritage alone Ceannt merits our recognition.

As with so many others, Ceannt’s involvement in the Gaelic revival also awakened in him the realization that as a nation with a unique and rich heritage Ireland deserved its own government and independence. He was one of the founding members of the Irish Volunteers and immediately injected them with his energy and enthusiasm, quickly rising to the rank of Commandant of the 4th Battalion. He soon was also appointed Director of Communication and developed an effective and secure “postal system” for communicating. In one humorous incident, Ceannt formed the “Banba Rifle Club” as a cover for training the Volunteers in marksmanship and he wrote to the Miniature Rifle Association of Great Britain to be enrolled. When WW I broke out, the Rifle Association wrote to Ceannt asking him to encourage the member to “volunteer to fight for the cause of small nations”. No doubt even the intense Ceannt had a wry smile when he wrote back his assurances that “all the club’s members were willing to fight for the rights of small nations”, though likely not the “small nation” that the British Rifle association contemplated.

And fight for the small nation they did. On Easter Monday, April 24 1916, Ceannt and his battalion occupied the South Dublin Union. The was a workhouse and hospital complex spread over fifty-two acres. The Union was a strategically important position as it dominated the approaches to Kingsbridge Railway Station, Richmond Barracks and Islandbridge Barracks. From the beginning, Ceannt and his men were involved in fierce of some of the most savage kind as they engaged the British forces in the labyrinth of buildings. The intensity of the fighting can be gauged by the fact that Ceannt’ second-in-command Cathal Brugha suffered over twenty life threatening wounds and yet still held his barricade while singing “God Save Ireland”.

The Volunteers under Ceannt continued to hold their position until ordered to surrender on Sunday, April 30. When a British Officer presented himself to accept Ceannt surrender, he was shocked to see that the British forces had been fought to a standstill by a garrison of only forty men. In a sign of respect, the Officer allowed Ceannt and his men to march with their arms to the surrender point at St. Patrick’s Park; the dignity that Ceannt and his men showed even in defeat was admired by many.

Eamonn Ceannt was executed by a British firing squad in the early hours of Monday, May 8, 1916. Among his last words is a call to action for us in the Centennial year of 2016

“Ireland has shown she is a Nation. This generation can claim to have raised sons as brave as any that went before. And in the years to come, Ireland will honour those who risked all for her honour at Easter 1916.”

In 2016, let us unblushingly and without apology honor Eamonn Ceannt and the great men and women of 1916

Neil F. Cosgrove, Historian