Alfred “Al” Smith was born on 174th South Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the area where he resided his entire life. He was the son of Catherine (née Mulvihill), the daughter of Irish immigrants from County Westmeath, Ireland, and Joseph Smith, the son of an Italian immigrant; Smith would always identify with his mother’s Irish heritage. The family was one of many that struggled financially in what was known as the “Gilded Age,” which transformed New York. The Brooklyn Bridge, considered one of the great symbols of New York’s renaissance, could be seen from the Smith home. Smith recalled, “The Brooklyn Bridge and I grew up together.”

Smith’s father died when Al was 13, forcing him to drop out of school and take a job at the Fulton fish market to support his family. Smith never attended high school or college and claimed that everything he learned about people came from this experience. One skill Smith had taken with him from his interrupted education was his public speaking ability; he won an oratory contest when he was 11 and would hone his smooth oratory style that would become his signature in later life while performing in amateur theatrics.

Smith’s talents soon drew the attention of the Tammany Hall political machine, where in 1895, he was appointed to the Commissioner of Jurors. Despite his Tammany Hall connections, Smith himself remained untarnished by its pervasive corruption and scandals.

Smith was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1904 and was repeatedly reelected, serving through 1915. He gained notoriety for his work as the vice chairman of the state commission appointed to investigate the infamous 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that claimed the lives of 146 workers due to pervasive unsafe working conditions. His meetings with the families of the deceased Triangle factory workers left a strong impression on him, leading Smith to champion legislation to end dangerous and unhealthy workplace conditions.

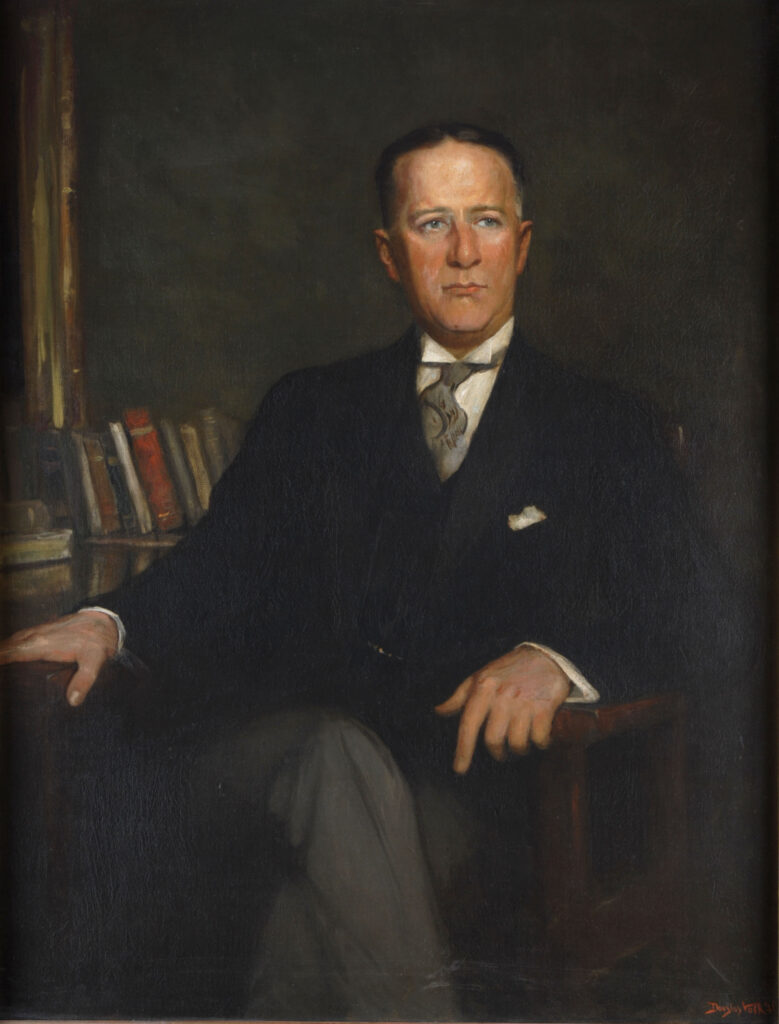

Smith went on to become the first Catholic to be elected governor of New York, a position he would hold for four terms. As governor, Smith campaigned for adequate housing, improved factory laws, proper care of the mentally ill, child welfare, and state parks. Simultaneously, Smith pursued reorganizing the state government to eliminate inefficiencies and run on a more business-like mode. He showed excellent leadership skills as a consensus builder, frequently getting support from the opposition Republican party.

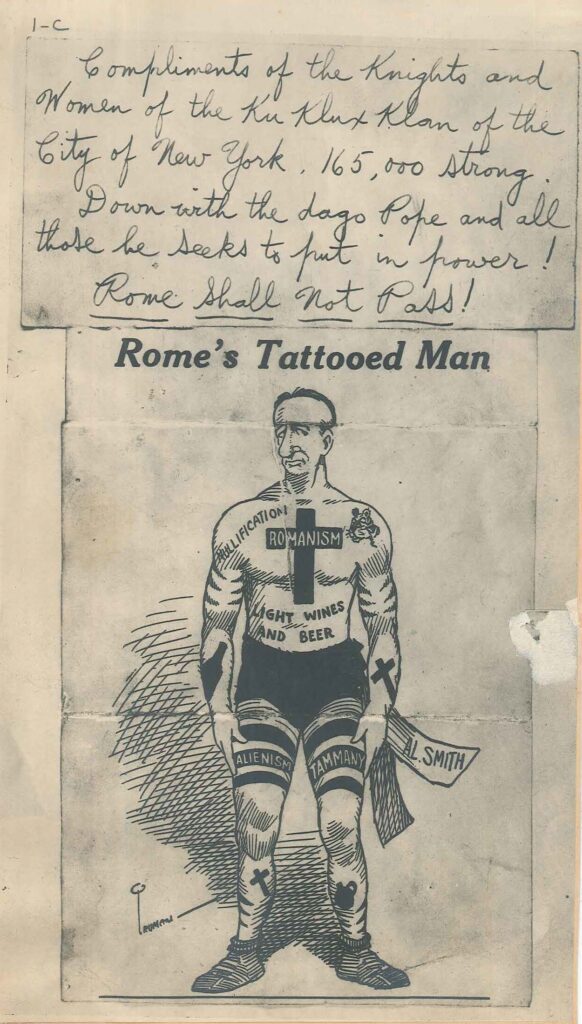

Sadly, while Al Smith was rising to prominence, a dark stain was spreading across America; the Ku Klux Klan. While still at its core anti-African American, since the end of WW I, the Klan had expanded from the South to become a nationwide movement fueled by an anti-Catholic/anti-Immigrant platform and anxieties over the rise to prominence of politicians such as Al Smith. At the 1924 Democratic convention held at Madison Square Garden, floor fights, sometimes literally, broke out between Klan and anti-Klan factions. A motion for the Democratic party to censure the Klan was defeated 546 to 542. Al Smith was nominated as the presidential candidate by future president Franklin Roosevelt, who in his speech christened Smith “the Happy Warrior of the political battlefield,” a nickname with Smith throughout his career. Opposing him was William G. McAdoo, the son-in-law of former President Woodrow Wilson, the president who had shown the movie “The Klansman,” later rechristen “Birth of a Nation,” in the White House. On Independence day, the tenth day of the convention, 20,000 Klansmen assembled in New Jersey to burn crosses and effigies of Smith. Finally, after two weeks and 103 ballots, the Democratic convention settled on a compromise nominee John Davis of West Virginia, who in November was defeated by Calvin Coolidge.

Four years later, Al Smith successfully secured the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1928 but was still confronted by a campaign where the focus was anti-Irish Catholic bigotry. The Atlantic Monthly published an open letter asking whether, as a Catholic, Smith could be trusted to uphold religious freedom. In the Midwest, a picture was circulated of Smith at the opening ceremony of the Holland Tunnel, claiming it was a tunnel Smith was building from the White House to the Vatican. The Fellowship Forum, a widely read periodical, declared, “The real issue in this campaign is PROTESTANT AMERICANISM VERSUS RUM AND ROMANISM.”

Al Smith lost the 1928 election in a landslide to Herbert Hoover in a campaign fueled by prejudice.

With his 1928 election defeat, Smith’s political career was effectively over. As if coming full circle to the days when as a boy, he watched the building of the iconic Brooklyn Bridge, Smith became president of Empire State, Inc.; the corporation that would build New York City’s most iconic symbol: the Empire State Building. Paying tribute to the forces that shaped him, construction of the building began on March 17, 1930, St. Patrick’s Day, with his grandchildren cutting the ribbon when the world’s tallest skyscraper opened on May 1, 1931, when international labor was celebrated. Under Smith’s guidance, construction was completed in only 13 months.

Smith returned to the national spotlight as a vocal critic of the Nazi movement in German and supported American intervention in the war. Smith was appointed a Papal Chamberlain of the Sword and Cape, one of the highest honors the Papacy bestowed on the laity. Al Smith would die in 1944 at the age of 70.

The career of Al Smith is both an inspiration and a warning. It is a reminder both that we were once “the others” in American society and the evils of prejudice. It is also a reminder that intolerance and anti-Catholicism have not gone away; it can still be heard in congress in during confirmation hearings and in recent news reports of a school administration refusing to hire Catholic teachers. It is an American story that should be taught widely.