It is an iconic image of WW II, a photo taken on June 6, 1944 showing American soldiers exiting a landing craft coming ashore at Omaha beach. A few months later on October 20th, another photo captured the moment General Douglas MacArthur “returned” to the Philippines, wading ashore from a landing craft. Neither of these historic moments would have been possible without one man, as overlooked but essential as the landing craft in these images that bore his name, Andrew Higgins.

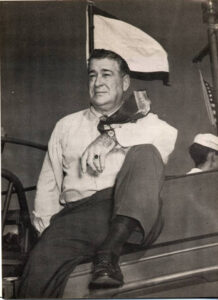

Though in later life Higgins would be inseparably identified with New Orleans, he was born in Columbus, Nebraska in 1886. Losing his father when he was but seven years old, Higgins would claim he received his determination and strong will from his mother whose ancestors had come from Ireland after the failed rebellion of 1848. Higgins demonstrated the industry and innovation that were to be his hallmarks at an early age. At the age of nine and with only a sickle he began a grass cutting business. He soon purchased a lawn mower, eventually expanding until he had seventeen mowers and was hiring older boys to do the work while he managed the business. An incurable builder, the young Higgins constructed an iceboat in the basement of his home for use on the nearby lakes. When finished, he realized it was too big to be taken out of the basement doors. With characteristic determination, he borrowed jacks from a nearby construction site and with friends removed a section of the basement’s wall, got the boat out and restored the wall, all while his mother was out shopping. Perhaps not unexpectedly, such creativity, determination and strong will often brought young Higgins into conflict with school authorities resulting in him being expelled before graduating.

Higgins moved to the south where he began working in the lumber industry. His interest in boats was again rekindled when he was confronted with the problem of how to access timber from shallow, obstacle choked bayous. Higgins took a correspondence course in naval architecture and soon designed the first of the flat-bottomed shallow draft boats which would make him famous. The key feature was that the propeller was incorporated in a recessed tunnel that protected the propeller from grounding and fouling.

In the late 1930’s Higgins owned a small shipyard in New Orleans servicing the need of loggers and oil drillers in the Mississippi Delta. The

growing threat of war soon drew the interest of the Marines in Higgins’ boats as the Navy Bureau of Ships had consistently failed to produce craft that could effectively deliver Marines, their tanks and artillery on a beach. Marine General Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith had seen trials of Higgins shallow draft “Eureka” boat could be “an answer to the Marine prayer”. The one concern was that as configured the Marines would need to disembark the boat going over the side, slowing their exit when they were most vulnerable. At his own expense, Higgin’s modified the boats by cutting off the bow and replacing it with a ramp. Higgins received a call that the Navy that they and the Marines would be coming to New Orleans to test the ramped boats and Higgins should also prepare to discuss a design for a craft capable of landing tanks. Higgins informed the Navy that instead of a plan he would have a workable craft. “It can’t be done,” the Navy told him; “The Hell it can’t,” replied Higgins, “you just be here in three days”. Higgins had the boat built in 61 hours. Both would be taken into service, and while the ramped “Eureka” would have the official designation of LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel) it would be known universally as the Higgins Boat.

Higgin’s answer to the “Marine prayer” came just in time as the United States would soon enter WW II. With his tireless energy, often working 16 hour days, Higgins seemingly overnight turned his small 50 man New Orleans boat building business into one of the largest boat builders in the world, building not only several models of landing craft but other boats as well. By September 1943, 12,964 of the American Navy’s 14,072 vessels had been designed by Higgins Industries. Hitler bitterly called Higgins “The new Noah”. A fact that should not be overlooked is that to achieve this prodigious output Higgins employed anyone capable of performing the job, irrespective of gender or race, and everyone who performed the same job was given the same pay. Higgins was one of our nation’s first equal opportunity employers. Realizing the impact a worker lost due to sickness could have on productivity, Higgins established a company clinic where works could access health care free of charge.

Unfortunately, wartime gratitude is a fleeting thing. When the war ended, the drive and determination which had enabled Higgins to deliver what his country needed came back to haunt him as the toes he stepped on to get the job done now took their revenge. Maverick innovators like Higgins were out of place in the conformist world of post-war corporate America. Despite an indisputable record of being an advocate for his workers, his firms were crippled by post-war strikes. Higgins died in New Orleans on 1 August 1952.

Andrew Jackson Higgins was like the boat that bore his name: straightforward, tough and reliable. Neither was sophisticated, they just got the job done. He deserves to be remembered much more than he is. As General Eisenhower noted, “Andrew Higgins … is the man who won the war for us. … If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs, we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different.”

Neil F. Cosgrove, Historian